Following a decade of mostly rising stock prices, last year’s fourth-quarter correction of nearly -20% reminded investors that the stock market’s rewards come with substantial risk. Given weakening economic data in recent months, it wouldn’t be surprising if some investors are thinking it might be time to scale back any new investing (or even head for the exits altogether) and wait for the next bear market to pass.

Such timing moves are intended to improve long-term returns, but as we’ve explained before, that’s rarely the result. First, as the last few years have clearly demonstrated, it’s extremely difficult to time these moves correctly. But another reason is often overlooked — timing simply isn’t as significant a factor as most investors think.

The long-term stock investor prospers because he or she owns shares in businesses that participate in a productive economy. The important thing is not so much when you buy, but that you buy and continue to buy.

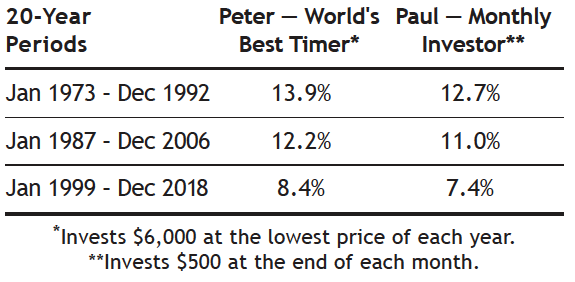

The table at right shows the results of two approaches, applied across three separate 20-year periods. Both Peter and Paul started each period with a balance of $60,000 and invested $6,000 more each year in an S&P 500 index fund, but they did it differently. Peter is the world’s best timer: every year he invested his $6,000 on the very lowest day of that year. Paul, on the other hand, simply divided his $6,000 into 12 parts and invested $500 on the last day of every month. The results shown assume dividends were reinvested.

Two facts stand out. First, they were both quite successful in all three periods. We specifically chose these periods to simulate today’s fears of investing new money immediately prior to some horrible market breakdown. The first period begins just as the famously difficult 1973-1974 bear market is about to start; the second begins with the infamous “Black Monday” drop of 22.6% only months away; and the last begins just prior to the bursting of the “dot-com” bubble. Second, the impact of even perfect timing — impossible to actually achieve — was minimal. Despite being perfect for 20 years, Peter’s annualized returns were just 1.0%-1.2% better.

It turns out you don’t need to have Peter’s timing skills (yay!) to see your capital grow handsomely in the market over time. Taking this idea one step further, another analysis compared buying on the best day vs. the worst day of each year. The result across multiple 30-year periods was that the very best timing portfolios ended only about 20% ahead of the very worst timing portfolios.

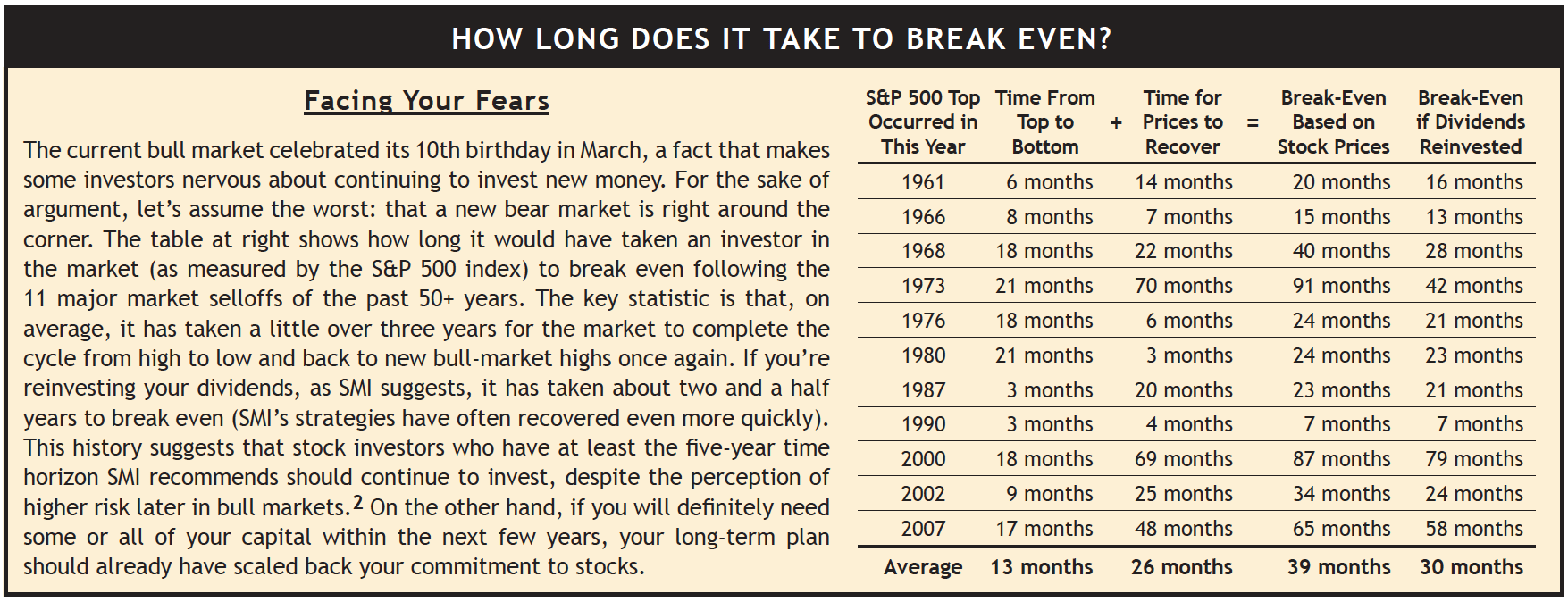

We thought it would be interesting to push this idea one step further. What if someone only bought infrequently, at the market high immediately prior to each big bear market?

Poor Percy also started each period with $60,000 and saved $500 each month, just like Peter and Paul. But Percy only mustered the nerve to invest his new money when each bull market reached its peak (prior to the 1973, 1987, 2000, and 2007 bear markets). His one saving grace was he never sold any of his holdings, but he would just save his monthly deposits in cash between bull market peaks. (Again, this is impossibly bad timing, but that’s the point of the exercise!)

Despite this horrible approach and the worst timing imaginable, Percy’s results weren’t as bad as you would think. In each of the three periods, his final portfolio total would have trailed Paul’s (the monthly dollar-cost-averager) by only about 25%.

Don’t misunderstand the point here. A 20%-25% gap in returns is clearly significant. But these examples provide us with a literal example of the “80/20 rule” — 80% of the returns came from simply being present in the market. Even the most impossibly good/bad timing parameters could only improve on those results by 20-25%, so the potential reward of a more realistic market-timing approach would be even less significant.

Timing in the SMI strategies

This is why timing plays a distinctly small role in SMI’s strategies. For most of SMI’s history, timing played no role at all. But our experience helping thousands of investors through the 2000 and 2008 bear markets has mirrored the behavioral research that has been done in recent decades. Specifically, the emotional toll of deep bear markets is extremely high for buy-and-hold investors. While some can hold on, many others eventually crack under the emotional pressure and make selling decisions that leave deep scars in their long-term returns. While “buy and hold no matter what” may be the simplest and purest ideology, it simply doesn’t work for many investors. So after the last bear market, we decided it would be better for that emotional pressure-release valve to be built right into our strategies, rather than being left to each individual investor.

As a result, there is now a small timing element involved in both SMI’s Dynamic Asset Allocation (DAA) and Fund Upgrading strategy. DAA really isn’t timing per se, but the fact that it rotates between six different asset classes does present the opportunity for DAA to be completely out of a given asset class (i.e., stocks) at certain times. Fund Upgrading received a “2.0” enhancement in 2018 which added a gradually implemented defensive protocol. Importantly though, the bar for this defensive protocol to be turned on is high — in our testing, it would only have triggered (even partially) three or four times in the past 30 years.

(See Higher Returns With Less Risk, Re-Examined to learn how combining SMI’s strategies can reduce overall portfolio risk without sacrificing much long-term return.)

This rarity is by design — we want Upgraders to know that if market declines are severe enough, protection will kick in via a predetermined, disciplined fashion. But we only want those defensive protocols triggering in the most extreme cases because most of the time investors are better off staying invested and simply riding out market volatility! Hopefully, knowing these defensive protocols are watching out for them will eliminate individuals trying to make timing decisions on their own.

Conclusion

The main takeaway here is simple: being consistent in your investing commitment (which anyone can do) is a much greater contributor to your long-term success than your timing efforts (which very few can do well). While superior timing can provide a small boost to your returns over the long haul, the true engine for capital growth is the steady increase of your ownership stake in American industry month after month. That’s why dollar-cost-averaging can be such a powerful tool for the average investor. You don’t need to possess great market experience or trading skills to invest successfully; you need only to be tenacious! It takes will power, not mind power.

Investors have had a fairly easy emotional ride in stocks for most of the past decade. Eventually, market storms will return — they always do. When that happens, you can expect most investors’ emotions will become as volatile as the markets. At that time, it’s crucial that you’ve trained yourself to ask the right question. Not questions like: “What’s the market going to do next?” Or, “How low might it go?” No one knows the answers to such questions. Instead, the correct question is: “What does my long-term strategy call for?” Importantly, if you’re investing via SMI’s strategies, you can simply continue to follow the monthly instructions, as any defensive “timing” decisions you’ll need are built right into their regular mechanics.

For now, if you’re following a dollar-cost-averaging program that calls for you to make monthly investments, then follow through — make your monthly investments as planned. If you have a diversified portfolio in place that reflects the amount of risk suitable for you over the next 5-10 years, then relax and look beyond any potential “valley” experiences in the short term.

The goal is to make “inside-out” decisions — ones based on your personal strategy (which you know) rather than on any speculation as to what the markets may do over the coming 6-12 months (which you will never know).

Click Table to Enlarge