With the April 15 deadline fast approaching, there’s still time to make tax-year 2018 contributions to an IRA — but not much.

So, we’re here to help you sort through common (and often confusing) questions related to IRAs, such as: “Do I even qualify for an IRA?”; “What’s the difference between a traditional IRA and a Roth IRA?”; “Should I convert my traditional IRA to a Roth IRA?”; “If I’m eligible to contribute to both, should I use an IRA or a 401(k)?”; and “Should I ‘roll’ an old 401(k) account into an IRA?”

The retirement income of most Americans rests on what’s been referred to as a “three-legged stool.” Retirement benefits from Social Security serve as one of the legs, historically providing 35%-45% of retirees’ monthly income. But the long-term funding issues facing the Social Security program (relatively fewer workers paying in, more retirees taking out) make it difficult to project with confidence the level of benefits that will be available years into the future (you can see your “estimated benefits” by creating an account on the Social Security website).

The second leg of the retirement-income stool is composed of employer-sponsored retirement plans. These plans provide about 15%-20% of today’s retirees’ monthly income on average. There are two main types. Some are traditional defined-benefit plans, in which workers are “guaranteed” a certain monthly income when they retire.

However, most are newer defined-contribution plans — such as 401(k) plans — in which workers make their own investment decisions from a list of options chosen by the employer. In these plans, the amount of money that will be available for a worker’s monthly income during retirement is uncertain. That’s because it depends on several variables, such as how much a worker contributes, whether the employer matches the employee’s contributions at some level, the quality of the investment options, and how successful the employee is at choosing profitable investments.

The third leg of the retirement-income stool is personal savings. It is this leg over which individuals have the most control, and is likely to play an increasingly important role in providing adequate retirement incomes in the years ahead. A key vehicle for building personal retirement savings is the Individual Retirement Account (IRA).

An IRA is not, in itself, an investment. It’s a tax-sheltered vehicle through which you make investments. As such, an IRA can hold most of the same investments any other account can hold: stocks, bonds, mutual funds, bank CDs — even gold. This means you can invest your IRA money along the same lines as the rest of your long-term investment plan, and use any of SMI’s strategies.

Two types of IRAs

The “traditional” IRA first appeared in 1974 when Congress voted to allow certain working persons — those not covered by a pension at work — to put away up to $2,000 a year for retirement and deduct it from their federal income-tax returns. Not only did IRA investors enjoy immediate tax savings, they were also excused from paying any current income taxes on the investment profits they made. Until they began withdrawing the money during retirement, they had the pleasure of watching their money grow tax-deferred. The IRA deduction was second only to the deductibility of home-mortgage interest as the best tax break available to middle-class taxpayers.

In 1997, Congress authorized a second type of IRA, the “Roth IRA.” This new option (named after Sen. William Roth, who sponsored the bill) differs from the traditional IRA primarily in the way taxes are handled: Do you want to pay them now or pay them later?

With a traditional IRA, you can take an immediate tax deduction for the amount you contribute (i.e., you save on taxes now). When the money is withdrawn down the road, that’s when you pay the income tax — on both contributions and gains. With a Roth IRA, contributions are not deductible (i.e., no up-front tax savings ). However, all of your future withdrawals, including your investment gains, are tax-free.

Contribution limits

Although traditional IRAs and Roth IRAs receive different tax treatment, certain ground rules apply to both types of accounts. One is that total contributions are limited to a certain amount per year. For the 2019 tax year, total IRA contributions are capped at $6,000 per person, unless you are 50 years old or over, in which case you’re allowed to contribute $7,000. Contributions may be split between a traditional IRA and a Roth IRA, but your overall contributions may not exceed the limit.

Those contribution limits are far lower than for a 401(k)-type workplace retirement plan, where employees can contribute $19,000 per year (or $25,000 if age 50 or older). However, keep in mind that if a husband and wife file a joint tax return, they can make IRA contributions for both the “working” spouse and the “non-working” spouse (not our choice of terms, we assure you!), providing that their combined earned income is at least as large as the IRA contributions made. It doesn’t matter how much each spouse earned, or even if one didn’t earn any income at all. So, for 2019, a married couple younger than age 50 could contribute a maximum of $12,000 ($6,000 for each) as long as their overall earnings were at least $12,000 during the year. The contributions must be made to separate IRA accounts, however, since there’s no such thing as a “joint” IRA.

Choosing between an IRA and a 401(k)

If you are eligible to participate in a 401(k), 403(b), or similar-type plan at work and your contributions are matched by your employer, don’t even consider an IRA until you are contributing enough money to your work-based plan to get the full amount of the employer match. That match is some of the easiest money you’ll ever make. In essence, it’s a guaranteed return on your investment. For example, if your employer will contribute 50 cents for every dollar you contribute (usually up to a limit, such as 6% of your salary), that’s a guaranteed 50% return!

Above the matching level, however, it often makes more sense to contribute to an IRA rather than contributing more to the 401(k). Why? Because of the greater variety of investment choices available in IRAs. Many employer-sponsored plans have only a handful of investment options from which to choose. That restricts your ability to create the kind of portfolio you’d like to have. With an IRA, on the other hand, the options are wide open.

So, get the “free money” of your 401(k) match first. Then, if you want to invest more than the amount of your salary that qualifies for the match, put those additional dollars in an IRA, assuming you qualify to contribute to one (our next topic). If you contribute the maximum to an IRA and still have more you want to invest for retirement, go back to your workplace plan and contribute more there.

Eligibility

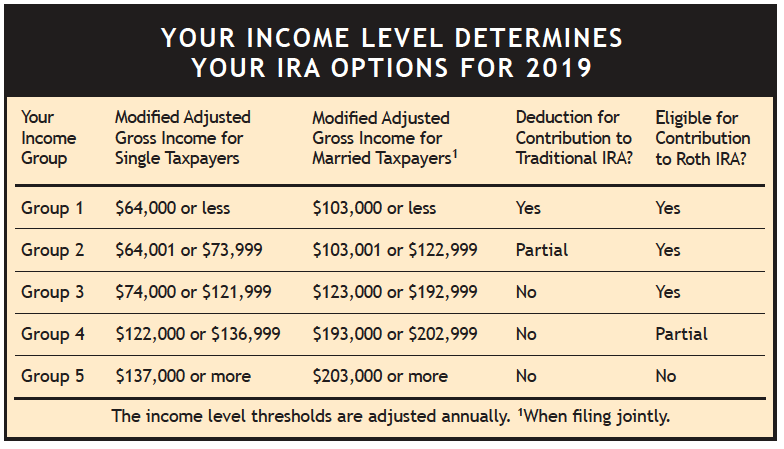

For traditional IRAs (contributions deductible, withdrawals taxable), whether you qualify to make deductible contributions depends on whether you are “covered” by a workplace retirement plan and how much Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) you earn. According to the IRS, you’re “covered” by an employer’s retirement plan if your company offers such a plan and you contributed to the plan or your employer contributed to the plan on your behalf. In the case of a defined-benefit plan, such as a traditional pension plan, if you’re eligible for the plan, you’re “covered.” IRS Pub 590-A has a worksheet for determining your MAGI.

The nearby table assumes you are covered by a workplace plan. If you’re not, see the next section for details on these two possibilities not shown in the table: You’re not covered by a workplace plan but you’re married and your spouse is covered (Group 6), or you’re not covered by a workplace plan and your spouse isn’t covered either (Group 7).

Click Table to Enlarge

For Roth IRAs (contributions not deductible, withdrawals tax-free), whether you qualify to make contributions at all depends on your income, as outlined in the table. Your participation in a workplace retirement plan does not matter.

Now consider the following general guidelines:

Group 1

If you are in this group, you have the greatest flexibility when it comes to your IRA options. You can choose to make either a fully deductible contribution to a traditional IRA or a non-deductible contribution to a Roth IRA. (We’ll touch on the “Traditional versus Roth” decision in a minute and the article Traditional IRA vs. Roth: Which Maximizes Retirement Income? will help you sort through that decision in greater detail.)

Group 2

You’re in the “phase-out range” where the government begins taking away your tax deduction for contributing to a traditional IRA. If you are married, filing jointly, and your Modified Adjusted Gross Income is more than $103,000 but less than $123,000, only a portion of your contribution is tax-deductible. Single taxpayers have a lower threshold at each step along the way, as can be seen in the table. However, Group 2 people are still fully eligible to contribute to a Roth.Group 3

You’re over the limit for a traditional IRA. Because your family income is $123,000 or more, you receive no deduction — unless neither you nor your spouse are covered by a retirement plan at work. You could make a non-deductible contribution to a traditional IRA, but why do that with the Roth option available? You’re Roth material all the way.Group 4

As with Group 3, a Roth is your best option. But you’re in the “phase-out range” where the government begins taking away your right to make a full Roth contribution. Still, take what you can get.Group 5

Sorry. Congress figures you don’t need any tax incentives to save for retirement. You’re on your own — no IRAs for you. (Well, that’s not strictly true. You could make non-deductible contributions to a traditional IRA, then convert those holdings to a Roth. More on this momentarily.)Group 6

This group, which isn’t represented in the table, is for anyone who isn’t covered by a workplace plan, but whose spouse is covered. You qualify for a full deduction for money contributed to a traditional IRA as long as your household income is $193,000 or less. If it’s above that threshold but below $203,000, you qualify for a partial deduction. At $203,000 of household income or above, you may not take any deduction.Group 7

Finally, all you folks who aren’t covered by a retirement plan at work (and, if married, neither is your spouse), you’re the exception to most of the rules. No matter which other group you’re in, you are entitled to a full tax deduction for any contributions you make to a traditional IRA. And unless you’re in Group 5, a Roth IRA is also an option.

Choosing between a traditional IRA and a Roth

To a great degree, what type of IRA to use depends on whether you expect to be in a higher tax bracket when you retire than the one you’re in now. When you’re just starting your career, your income usually puts you in a low tax bracket. With the assumption that you’ll be in a higher tax bracket when you retire — whether because of your retirement income, higher tax rates, or some of both — it usually makes the most sense to go with a Roth IRA. That way, you give up the tax break now while your taxes are low and take advantage of it later when your taxes are higher.

However, this tax-bracket question is not as straightforward as you may think. Other factors must be considered. (For more on the Roth vs. Traditional decision, see Traditional IRA vs. Roth: Which Maximizes Retirement Income?)

Other considerations

One drawback of a traditional IRA is it can have the effect of turning capital gains (currently taxed at lesser rates) into ordinary income (taxed at higher rates). That’s because, under current law, when you take money out of a traditional IRA, it all gets taxed the same way — as ordinary income — even though a sizable portion of your growth may have come from capital gains (the only exception being if you’ve made any non-deductible contributions). If your income is relatively high in retirement, having these gains taxed at your maximum regular income-tax rate (potentially as high as 37%) is painful.

This drawback of turning capital gains into ordinary income is typically only an issue if you’re buying and holding individual stocks or index funds (which are highly tax-efficient anyway). In those instances, you may be better off holding such assets in a taxable account. Generally speaking, if you have a mix of taxable and IRA accounts and want to own both stocks and bonds, hold the bond investments in the traditional IRA and the stock index funds or individual stocks you plan to hold long-term in the taxable account.

However, if you are following SMI’s active strategies (Upgrading, DAA, Sector Rotation, 50/40/10), you should keep your stock funds in the IRA due to the likelihood of their larger long-term gains and the fact that each trade would be taxable right away otherwise.

Withdrawing funds from an IRA after age 59½

With a traditional IRA, this is the age at which penalty-free withdrawals of contributions and earnings are allowed. Of course, you’ll owe ordinary income tax on those withdrawals since you received a tax deduction for your contributions. At age 70½, withdrawals are required. Your required minimum distributions (RMDs) are based on your age and account balance. (The IRS has a worksheet to help you determine the amount). The penalty for not taking RMDs is substantial — 50% of the RMD amount — so be sure to take those distributions. Age 70½ is also the age at which you are no longer allowed to contribute to a traditional IRA.

With a Roth IRA, you can withdraw the principal you’ve contributed at any time for any reason without facing income taxes or penalties (because you already paid income tax on the money you contributed). Whether you can withdraw earnings tax-free depends on whether you have met the standards of the five-year rule.

The rule states that you must have contributed to a Roth IRA (any Roth IRA, not necessarily the one you want take a withdrawal from), in January of the calendar year at least five years prior to the year in which you would like to take the withdrawal. Want to take a withdrawal of earnings in July of this year? You would have had to contribute to your first Roth in January of 2014 or earlier.

Two benefits that are unique to Roth IRAs are that you never have to make withdrawals (Roth account holders are not subject to RMDs) and you never have to stop making contributions. So, if you don’t need the money in your Roth IRA for living expenses, you can continue to let the money grow tax-free for the benefit of your heirs or favorite charities.

Withdrawing funds from an IRA before age 59½

With a traditional IRA, early withdrawals may be made penalty- but not tax-free under the following circumstances: death, disability, high medical expenses, medical insurance premiums while unemployed, qualified higher education expenses (for you, a spouse, child or grandchild), or first-time homebuyer expenses up to $10,000 (a couple of other allowable circumstances are described in IRS Pub 590-B). If you make an early withdrawal outside of those situations, you’ll be subject to income tax on the full amount and a 10% penalty.

Roth IRAs offer more flexibility than traditional IRAs when it comes to early withdrawals. As noted earlier, you’re always free to withdraw the principal you’ve contributed to a Roth. Investment gains also may be withdrawn before age 59½ without penalty (though regular taxes will still apply) if 1) the withdrawal is related to any of the reasons listed above for early withdrawals from a traditional IRA and 2) if the “five-year rule” conditions described earlier are met.

What about converting a traditional IRA to a Roth?

A law that took effect in 2010 allows such conversions, regardless of income level. Converting from a traditional IRA to a Roth will enable you to enjoy tax-free withdrawals of your investment gains when you retire (rather than paying deferred tax on those gains as you would when making withdrawals from a traditional IRA). In addition, converting can help you manage and reduce your future required mandatory distributions (RMDs). As stated earlier, with traditional IRAs, RMDs begin the year you reach age 70½. With Roth IRAs, there are no RMDs.

Of course, you’ll have to pay income tax on the money you convert (the only exception would be any non-deductible contributions you made, but most IRA account holders haven’t done that), so if possible, doing a conversion in a year when your tax rate is relatively low would be ideal. You can convert as much or as little as you want each year — it’s not an all-or-nothing deal.

Whether to convert a traditional IRA to a Roth is a question that deserves considerable thought because it may affect other aspects of your tax picture. For example, you might trigger the alternative minimum tax (although that’s far less likely under the new tax code that went into effect in 2018) or reduce eligibility for certain tax credits.

Is it worth converting? If you have the resources to pay the extra taxes without having to use any of the IRA balance to do so, it may be. But again, because a conversion may affect other aspects of your overall tax picture, don’t make a decision without considering all the implications.

If you do have the cash on hand to pay the taxes and converting looks appealing to you, there are two more questions to consider. First, are you likely to need the money five years or more before you turn 59½? With money converted from a traditional to a Roth IRA, it isn’t just the earnings that are subject to the five-year rule; all of the money is. After age 59½, only the earnings are subject to the rule. Second, are you absolutely certain you want to do an IRA conversion? Under the new tax code, a conversion cannot be undone.

Should you move 401(k) money to an IRA?

Most of today’s workers hold multiple jobs in the course of their careers. One result is that people often find themselves with multiple retirement accounts. There’s your old 401(k) from Glad-I-Left Corp., the traditional IRA you opened with your 2010 bonus check, your current company’s retirement plan account, and the Roth IRA you opened last year. Plus, your spouse may have a similar assortment of accounts. What to do with them all?

Generally speaking, it makes sense to “roll over” old work-based accounts into IRAs. A rollover (that is the legal term in the tax code) is simply a tax-free distribution of cash or other assets from one retirement program that you then contribute to another retirement program.

The reason you would want to roll money from an old 401(k) into an IRA is that, as noted earlier, your investment choices usually are going to be much broader in an IRA. Besides that, many companies require former employees to move their holdings out of the company plan within a certain period after leaving the company’s employ.

(That said, if you have a 401(k) account with a company for whom you stop working at or after age 55, you may not want to automatically roll it to an IRA. In that situation, you can withdraw from the 401(k) penalty-free. This unique “early retirement” provision goes away if you roll the 401(k) money into an IRA.)

The term “rollover” can be a bit confusing because there are actually two types of rollovers. In one, the money you’re putting into your new IRA comes from a qualified employer plan such as a 401(k). For this type of transfer, you should try to coordinate with your old company’s HR department and your new IRA custodian. The big fund companies and financial institutions handle these transactions all the time and can walk you through this normally painless process.

In the second type of rollover, you are moving an existing IRA from one company to another. While it’s possible to have the old custodian write a check which you then reinvest in a new IRA yourself (within a 60-day deadline), that is not what we recommend. Instead, it’s better to have the company you’re transferring to handle the process for you. This is called an IRA asset transfer (sometimes called a trustee-to-trustee transfer). A transfer of funds from your old IRA directly to your new one is not only simpler, but it also avoids any potential problems associated with missing the 60-day deadline.

If you have multiple IRA accounts, consider combining them into one. By combining accounts, you’ll save on fees and reduce paperwork. More importantly, you’ll have an easier time managing your investments and tracking their performance.

Conclusion

The next generation of retirees will be strongly reliant on personal savings for retirement income. Individual Retirement Accounts — both traditional and Roth — are helpful tools for building those savings. Maximizing your IRA savings opportunities should be a high financial priority. The combined benefits of tax-advantaged treatment and investment flexibility make IRAs tough to beat.