During the second half of the 20th century, going to college became the assumed “next step” for students graduating from high school. A bachelor’s degree is now routinely viewed as a prerequisite to a successful career.

But some influential educators, economists, and researchers — along with some parents and students — are re-thinking the “college for all” expectation. The reassessment is driven in large part by the exploding cost and related debt associated with earning a degree.

How’s this for a provocative statement? “Two-thirds of people who go to four-year colleges right out of high school should do something else.” So argues former U.S. Secretary of Education William J. Bennett. “Rather than simply swallowing the conventional wisdom and following the conventional path,” Bennett writes in Is College Worth It?, “more students need to make realistic assessments of their abilities and finances and then decide the best path for themselves.”

The need to make a realistic assessment of finances is stressed as well by scholar Peter Cappelli, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, in his book Will College Pay Off? “The relevant question should not just be whether there are benefits to graduating from college — surely there are — but also whether the financial benefits of those degrees are actually worth the cost of attending college,” he writes. “We should not kid ourselves about the risks associated with the biggest financial decision many families will ever make.”

As for the need to make a realistic assessment of a young person’s academic abilities when considering college, social scientist Charles Murray addressed that point forcefully a decade ago in his influential work Real Education. After examining SAT scores and other data related to student skills, Murray concluded that most students enrolled in four-year Bachelor of Arts programs probably shouldn’t be in college at all. Their gifts lie in areas other than the academic. (Murray also argued that except in fields such as science and engineering, a bachelor’s degree is no longer a reliable measure of whether someone is truly educated.)

The views articulated by Bennett, Cappelli, and Murray go against the grain. For decades, the conventional wisdom has been that (1) going off to college to earn a B.A. is the natural next step for high-school graduates, and (2) such a degree is the basic qualification for a well-paying job.

Economist Richard Vedder, Distinguished Professor of Economics Emeritus at Ohio University, believes the conventional wisdom is faulty. He points to a growing “mismatch between labor market realities and college graduation rates,” noting that “only about 40% of those entering college full-time end up graduating and taking jobs requiring the skills normally expected of college graduates.”

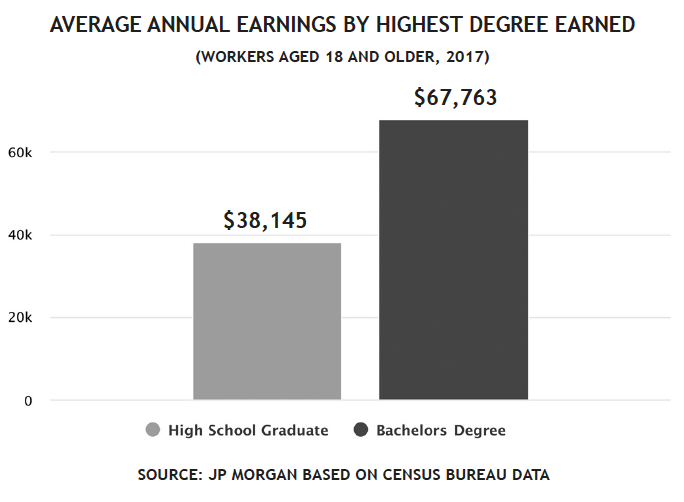

Of course, those who believe that attending college is still the best option for most young people can point to statistical measures too. A return-on-investment analysis (PDF) by researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York concluded that even though today’s “college students are paying more to go to school and earning less upon graduation,” investing in a college education “still appears to be a wise economic decision for the average person.” The analysis points out that “employers are willing to pay a premium for college graduates relative to those with just a high school diploma, even in jobs that are not typically considered college level positions.”

Click Graphic to Enlarge

That finding is consistent with the results of a 2014 Pew Research study titled “The Rising Cost of Not Going to College”: “On virtually every measure of economic well-being and career attainment...young college graduates are outperforming their peers with less education,” the Pew study found.

It is worth noting, however, that according to the U.S. Department of Education, about 40% of students who start college never finish — or at least don’t finish in a timely fashion (i.e., within six years). In his 2015 book, Will College Pay Off?, Peter Cappelli, professor of management at the University of Pennsylvania, warns that “it’s hard to get a return from going to college if you don’t finish college, and a lot of people don’t.”

Putting statistics in perspective

Aggregate data related to the earnings and employment status of college graduates tell us little about the experience of specific graduates or even groups of graduates. A more informative measure filters the data by areas of education specialization. Not surprisingly, outcomes differ across college majors. “In particular, students majoring in fields that provide technical training, such as engineering or math and computers, or fields geared toward growing parts of the economy, such as health care, have tended to earn higher returns on their educational investments,” notes the Federal Reserve Bank of New York study cited earlier.

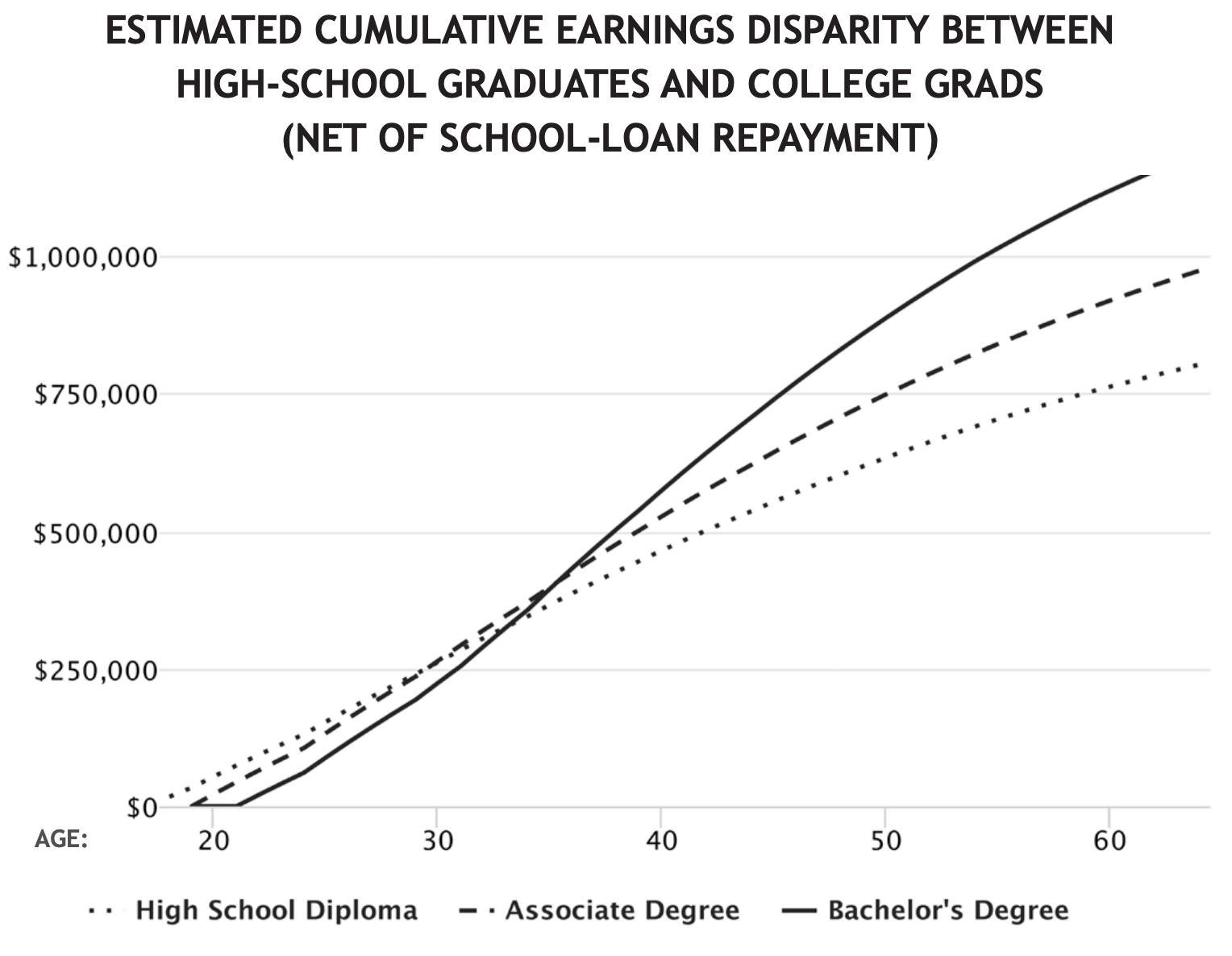

Earnings data, however, must be placed into a larger financial context. A person earning plenty of money but carrying high expenses isn’t much better off than one earning less but with lower expenses. Therefore, earnings after college must take into account the cost of getting a degree, especially if a significant portion of a graduate’s income is going toward repaying school loans for many years.

Click Graphic to Enlarge

According to the College Board (PDF), when loan-repayment amounts are subtracted from gross earnings, college graduates are at a net income disadvantage relative to high-school-only graduates for more than a decade after completing a bachelor’s degree (see graph).

On average, it requires 12 years in the full-time workforce for the typical B.A. recipient who has borrowed money for college to reach cumulative net-pay parity with a high-school-only graduate. This is not only because of years of school-related debt payments after graduation, but also because college students forgo full-time income for several years while earning a degree. Eventually, as seen in the graph, the cumulative net earnings of college graduates (including those with two-year degrees) begin to outperform the earnings of those with only a high-school education and continue to do so.

The growing debt burden

Most college students today incur education debt and the amounts borrowed are rising. A study (PDF) by the Institute for College Access & Success found that nearly two-thirds of students who earned a bachelor’s degree in 2019 used loans to help pay for college.

For those graduating with school debt, the average debt load — not including any loans taken out by parents — was $28,950, more than 50% higher than for students who graduated 15 years earlier. (Note: The sharpest increases in average indebtedness occurred between 2008 and 2012.) Assuming a standard payoff schedule and an average interest rate of 4.50%, the payment needed to retire that level of debt would be $300/month for 10 years.

The shifting cost/benefit picture

What are today’s students (and their parents) getting for their college-education outlay? That question isn’t easy to answer. For one thing, it can be difficult — especially early in the process — to get a clear picture of the true dollars-and-cents cost of attending a particular school. Although each college has a per-year (or per-semester) “sticker price,” few families actually pay that price. The sticker price is discounted by means of institutional grants, scholarships, and other aid.

How much aid a student receives depends on several factors, including the student’s academic or athletic prowess, the family’s overall financial situation, and a particular school’s ability to offer institutional aid. To help prospective students get a somewhat clearer view of the final cost, the U.S. government requires all colleges and universities to post on their websites a “net price calculator“ that estimates the level of aid.

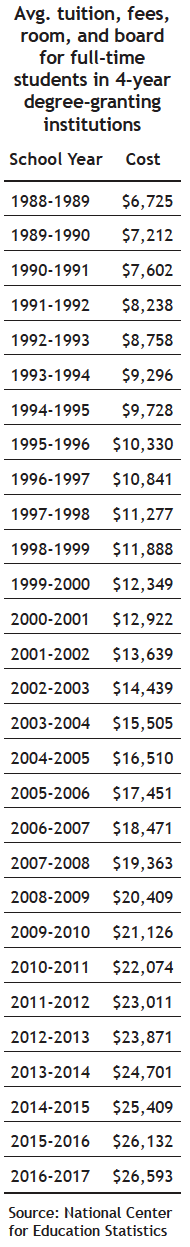

Even though sticker prices are often discounted, those prices remain the “baseline“ from which any institutional aid will be subtracted. Therefore, increases in sticker prices are a reliable indicator of the pace at which the cost of attending college is rising. The table at right shows the increases in average annual sticker prices over the past 30 years — at a rate nearly three times that of overall inflation.

In a market economy, steady price increases are difficult to maintain without an accompanying increase in quality. People may be willing to pay more for an upgraded product, but they balk at paying more for a product that hasn’t improved or perhaps has declined in quality. Thus far, however, higher education has been able to turn basic economics on its head. Demand for a college education remains high despite abnormal price increases (in comparison to the overall economy) and even though there is little indication that those investing in a college education today are getting an improved product over what was available decades ago.

To be sure, colleges have implemented technological advancements and expanded facilities, but the quality of the education itself is no better — and in some areas it is worse — than it used to be, according to a 2011 book titled Academically Adrift by sociologists Richard Arum and Josipa Roska. They found that nearly half of college students showed “no statistically significant gains in critical thinking, complex reasoning, and writing skills“ in their first three semesters. That finding buttressed the conclusions of an earlier report by the Commission on the Future of Higher Education which found “disturbing signs“ that “many students who...earn degrees have not actually mastered the reading, writing, and thinking skills we expect of college graduates.”

The apparent lack of academic rigor at many colleges may be disconcerting, but even more alarming is what many students are learning. As William Bennett writes in Is College Worth It?, “In today’s colleges, much of what is taught in the humanities and social sciences is nonsense (or nonsense on stilts), politically tendentious, and worth little in the marketplace and for the enrichment of...mind and soul.”

Yet despite concerns about cost, quality, and content, consumer demand for a college education remains strong — driven in part by abundant financial aid available to students. Beyond the institutional aid offered by colleges themselves, the federal government and the states serve up an alphabet soup of grants, loans, and work-study programs. While such aid surely makes college more accessible for some, the perverse overall effect is to drive prices even higher.

As government aid swells college coffers, the money typically is spent on the expansion of faculty, staff, and facilities. This results in ongoing higher costs for running the institution. These increased costs, “inevitably [put] upward pressure on tuition,” notes Andrew Gillen, an adjunct professor of economics at Johns Hopkins University, “setting the vicious cycle in motion all over again.”

The times they are a-changin’

The late economist Herb Stein once wryly observed, “If something can’t go on forever, it won’t.” Applying Stein’s Law to the higher-education marketplace, it seems clear that the model of rising costs and stagnant (or reduced) quality isn’t sustainable. The ways in which higher education will change n the years ahead, however, remains unclear.

What is clear is that the “full-time residential model of higher education is getting too expensive for a larger share of the American population” — to use the language of a report from the Chronicle Research Service, affiliated with the Chronicle of Higher Education. The report notes “more and more students are looking for lower-cost alternatives.”

So far, they are finding such alternatives in — among other things — online learning, hybrid class schedules (part in-class, part online), and the growth of for-profit colleges (where market discipline helps hold down costs). Further, some colleges are responding with options such as three-year degrees — i.e., accelerated programs — and no-frills satellite campuses (since you’re not getting access to the new student lounge and a state-of-the-art fitness center, you don’t pay for it).

As an example of online learning, Penn State’s World Campus now offers 36 web-based bachelor’s programs. If taken on campus, most courses in these majors would cost $866 per credit hour for a Pennsylvania resident or about twice that for out-of-state students. Online, however, the standard per-credit-hour cost is about $560 — no matter where the student lives.

Many established colleges and universities now have similar online programs. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, about 15% of college students now attend school exclusively online while another 18% take a mix of classroom and online courses.

Two-year degrees

A lower-cost alternative that has been around for years is the two-year associate’s degree — typically offered by community colleges and junior colleges. Such degrees can be a cost-effective step up to the job market, but that isn’t always the case.

Most students who pursue an associate’s degree intend to use it as a stepping stone to a bachelor’s degree. Unfortunately, only about 10% of such students actually go on to complete a B.A., according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. As a result, these students end up with a generalized “sub-baccalaureate” degree (in liberal arts or “general studies,” for example), rather than a degree that demonstrates proficiency in specific, marketable skills.

In contrast, some associate’s programs are aimed at preparing students for particular career fields, such as information technology, manufacturing, and health services. A 2018 report (PDF) from data-analytics firm Burning Glass Technologies cites research which found that “graduates with associate degrees in STEM [i.e., science, technology, engineering, mathematics], nursing, and construction earned a significant payoff compared with associate degrees in the humanities.”

The better outcomes for holders of specialized associate’s degrees is because jobs that require post-high school training but not a four-year college degree are reasonably plentiful. A 2017 study (PDF) by the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce found that “30 million good jobs [in the U.S.] do not require a bachelor’s degree. These good jobs pay an average of $55,000 per year, and a minimum of $35,000 annually.” The report notes that while many “good” jobs once required only a high school education or less, “the new good jobs almost all require at least some postsecondary education and training…. [In filling these] jobs, employers favor those with associate’s degrees or some college.”

However, Peter Cappelli, author of Will College Pay Off?, says students should be wary of four-year degree programs focused on specific vocational-type training. “These narrow, vocational degrees lock students into a single occupation, and [young people] often have to make that decision at age 17 when they apply for college. They may change their interests and want to switch fields, which may be hard to do in these practical programs.”

Considering the options

Post-secondary education is an investment — and it involves risk, especially if large sums of borrowed money are involved. To manage that risk, parents of today’s (and tomorrow’s) teenagers should at least re-think the assumptions that have guided post-high-school choices for decades.

Is earning a four-year bachelor’s degree the best choice? It may be, depending on your child’s gifts and field of interest. If so, is going the route of a high-cost residential program worth it? Again, it may be — perhaps especially for the intangibles that don’t show up on the tuition bill, including the very real possibility of finding a husband or wife.

As a parent, you must prayerfully consider the hard question: “Will my son or daughter be best served by going off to college in pursuit of a bachelor’s degree, or should we take a different approach to post-high school education?”

What about earning a bachelor’s degree online or in a hybrid part online/part on-campus program? Would it be better for your student to live at home and (at least initially)pursue a degree at a “commuter college“? Would a specialized two-year degree be sufficient? Should your son or daughter consider a lower-cost (and perhaps more-marketable) education at a vocational school — or maybe a certification program in an area such as accounting or computer programming?

Ideally, parents and their older teens will work together to make (in the words of Bill Bennett) “realistic assessments of...abilities and finances.” As together you seek to discern a wise course of action, consider the following ideas:

Wait and Work

No rule says a high school graduate must immediately enroll in college. Perhaps your son or daughter would be better served by taking a year to work and save. During that time, he or she can gain workplace skills, grow in maturity, and seek the Lord about the next step.Know Thyself

One of the best ways for parents and students to gain confidence in making educational and vocational decisions is to get a clear picture of the young person’s personality, skills, interests, and what type of work he or she is likely to find most satisfying. Among the assessments that provide this kind of information is Career Direct, an online assessment tool from Crown Financial Ministries. Reviewing the results may make the “next step” much clearer.Research and Reflect

If your child does want to pursue a four-year degree at a residential school, keep in mind that cost — although important — is only one factor among many. Other factors include location, size, and spiritual life. Visit campuses if possible and ask plenty of questions.Take Tests

You can cut the cost of college significantly if your son or daughter can pass Advanced Placement (AP) or College Level Examination Program (CLEP) tests, both offered through the College Board. Students who pass these tests can gain full credit for certain courses at a fraction of the cost of tuition. (Note: Many high schools offer Advanced Placement courses to help students prepare for AP tests. Not all colleges offer credit for AP and/or CLEP test results.)Make a Transfer

Another option for reducing the cost of a four-year degree is to go to a community college for the first two years, then transfer to a four-year school. (Check ahead regarding which courses will transfer!) Keep in mind that failing to follow through with completing a bachelor’s program is likely to hamper job prospects.Search for Scholarships

You can search online via the College Board and Peterson’s. Also, go your local library and look through The Scholarship Handbook (published by the College Board) and similar books that list available scholarships.Consider the Military

Military life isn’t for everyone, but entering the armed services is an excellent way to gain a solid education at low or no cost, while also serving the nation.

As you consider the options, remember we serve a God who made each of us for a purpose, and He is fully able to guide us toward fulfilling it. “For it is God who is working in you, enabling you both to will and to act for His good purpose“ (Philippians 2:13).