An old proverb, variously attributed, says: "A lie can travel around the world and back again while the truth is lacing up its boots."

In other words, false information travels fast, but the truth much more slowly.

The above-quoted proverb has been in use (in one form or another) for at least 300 years, demonstrating that people’s willingness to believe what is false — and to pass it on — existed long before someone coined the phrase "fake news."

Sometimes false information is malicious. Other times, it is the result of an honest mistake.

The estimable Wall Street Journal made such a mistake last week, related to investor behavior during and following the "coronavirus crash" that unfolded in February and March.

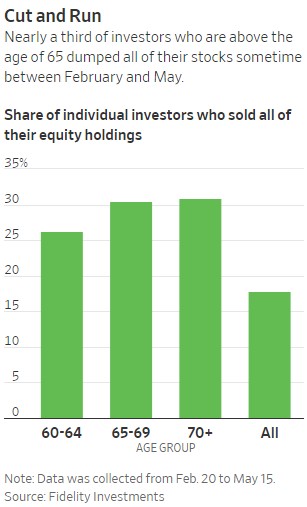

The paper reported, based on data from Fidelity Investments, that "nearly a third of investors ages 65 and up and 18% of all investors sold all of their stockholdings some time between February and May." The bar-graph shown at right accompanied the article.

Well-known investing bloggers repeated the startling statistics, including one who trumpeted the story with the headline: "One Out of Five Investors Sold All of Their Stocks."

A publication for financial advisers also picked up the story, and two prominent investing pundits did a podcast about the numbers.

But the Wall Street Journal reporter (and probably an editor or two) had misread the data. The numbers were wrong — far wrong.

Late last week, the WSJ issued a correction:

Of the 7.4% of investors ages 65 and up who made a change to their portfolios between February and May, nearly a third moved some money out of stocks, according to Fidelity Investments. Also, of the 6.9% of investors across all age groups who made a change to their portfolios between February and May, 18% moved some money out of stocks.

A Business & Finance article [on June 16] about older investors incorrectly said that nearly a third of investors ages 65 and up and 18% of all investors sold all of their stockholdings some time between February and May.

The differences between the initial report and the corrected report are huge. Eighteen percent of investors didn’t sell all their stocks during the time period mentioned. Only 6.9% made any changes in their stock holdings at all. And of that 6.9%, about one-fifth sold some (not all) of their stocks. So, in other words, during time period in question, slightly more than 1% of investors sold some stocks.

As for older investors (65+), one-third did not flee from the market, as initially reported (and repeated). Instead, only about one investor out of 13 made any changes at all. And of that relatively small number, about one-third moved a portion of their portfolios out of stocks. Put another way, the percentage of age 65-and-up investors who moved any of their money out of stocks was about 2.5%.

Attracting attention

In addition to honest errors such as the one the WSJ made (and don’t be too harsh, we all make errors), some people write or say things that aren’t entirely true for the purpose of attracting attention. After all, attention can sell books and build web traffic.

On a recent podcast, financial guru Suze Orman offered this advice: "If you have the ability to do a Roth 401K, 403B, or a TSP, or a Roth IRA, those are the type of retirement accounts that you want to be in. Stay away from the traditional [accounts]..."

That’s not a lie exactly, but it is an over-generalization that can be misleading. A more balanced approach would have been to say, "If you have the ability to do a Roth 401K, 403B, or a TSP, or a Roth IRA, those a great options. Traditional accounts are good too, but the Roths do have an attractive advantage when it comes to taxes. However, for older investors in a high tax bracket, a traditional IRA or 401(k) may make more sense..."

Of course, saying it in that nuanced way doesn’t attract attention. All it does is convey reliable information!

Don’t overreact

One of SMI’s key bits of advice through the years is to be "an inside-out investor." In other words, don’t let yourself be so shaped by what you see, read, or hear that you make decisions based on those always-changing outside influences rather than on your long-term plan and goals.

Sometimes the information you get — even from usually reliable sources — may be faulty. In other cases, a person giving information or advice may have an ulterior motive or a vested interest.

Whatever the case, don’t give way to a herd mentality that has you joining the crowd of those easily swayed by the latest bit of information.

Take everything with a grain of salt, and don’t overreact or react too quickly. In fact, when it comes to whatever the latest bit of information may be, most of the time, the best thing for a long-term investor to do is nothing at all.