A data thief who recently targeted credit-card issuer Capital One gained access to an estimated 80,000 bank account numbers and 140,000 Social Security numbers. Although the alleged hacker was captured and Capital One insisted that it is “unlikely that the information was used for fraud or disseminated,” the theft — like the massive 2017 data breach at credit-reporting agency Equifax — underscored the importance of finding out what’s showing up in your credit reports. Any person who gains access to your personal information could steal your identity and run up charges — or open new credit accounts in your name.

Even if credit fraud weren’t a concern, checking your reports at least once a year is wise. A Federal Trade Commission study (in 2012) discovered that about one credit report out of every four contained errors.

The particulars in your credit files can affect everything from your employability to your insurability, so inaccurate information — something as simple as a mistyped number or a missing paid-in-full notation — could spell trouble. Credit-report data also serve as the basis for your credit “score,” a metric of creditworthiness that affects your access to credit and the interest rates you’ll pay.

Free once a year

By law, you’re entitled to a credit report annually, at no cost, from each of the three major credit reporting bureaus: Experian, TransUnion, and Equifax. You can request your reports and download them via annualcreditreport.com.

(Although other websites offer free credit reports, the reports typically are from just a single bureau. Such sites also attempt to “upsell” users into paying for additional services such as credit scores, credit monitoring, and ID-theft protection.)

Annualcreditreport.com offers the option of requesting a single report (i.e., from just one bureau), two reports, or all three. (Note: Credit information is tied to one’s Social Security number, so there is no such thing as a joint credit report. If you’re married, both of you should request reports.)

If you want to monitor your credit activity on an ongoing basis, you may wish to stagger your requests, asking for one report every four months. That’s a good “maintenance” approach for those who already have cleaned up their credit files and aren’t planning to apply for a mortgage or other loan in the near future.

However, if you are planning a purchase that will involve a loan, it’s probably better to request all three reports at once. That way you can scan each report for errors and ask for any needed corrections before applying for the loan. (Keep in mind that each bureau works independently, so just because you don’t see any issues in one report doesn’t mean issues aren’t lurking in the others.)

Unfortunately, getting your free reports online doesn’t always work. Before allowing access to a report, the annualcreditreport.com website poses a series of multiple-choice security questions related to accounts you have (or may have once had) or about the names and locations of relatives. If you get an answer wrong, you won’t be offered a second chance. Instead, you’ll be instructed to request your report by regular mail, and you’ll have to supply documentation via mail (such as a recent W-2 form and a copy of your driver’s license) that verifies your identity. As if that’s not inconvenient enough, receiving a report by mail typically takes several weeks.

Reading your report

When you get a credit report, look it over to make sure your personal information is accurate and that you recognize all the credit accounts listed. If you see any you don’t recognize, that may be a sign of identity theft.

As noted earlier, credit scores, although different from reports, are derived from credit-report data. The two most widely used scores, each based on its own scoring model, are the FICO score (from Fair, Isaac and Co.) and VantageScore.

The FICO score is the one used by most lenders, so we’ll focus on that one. (Several large credit-card companies now offer free FICO-score access to their customers. Also see discover.com/free-credit-score.)

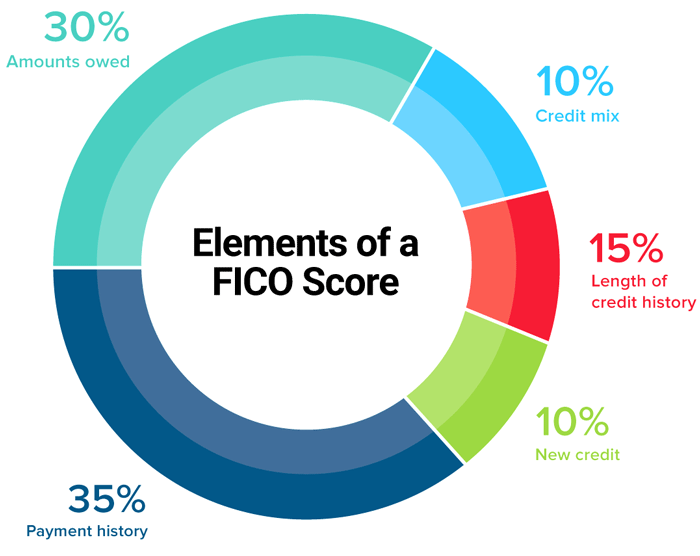

FICO’s primary scoring model takes five factors into account:

Payment History

This is the most important factor and accounts for 35% of your score. Each bureau, by the way, reports payment history differently.With Equifax, the ideal is for the “Status” of each account to be listed as “Pays as Agreed” and for “Date of first Delinquency” to be blank.

With Experian, you want the “Status” of open accounts to read “Current” and closed accounts to read “Paid.”

With TransUnion, you want the “Pay Status” to read “Paid or Paying as Agreed,” the “Past Due” section to read “0,” and “Rating” to read “OK.”

Amounts Owed

This relates to how much of your available credit you are using (i.e., “credit utilization”), and it determines 30% of your score. Once a month, the bureaus check to see how much you owe each creditor and compare that amount to your credit limit (regardless of whether you pay your balance in full each month). For example, if you have a credit card with a $10,000 credit limit and you’ve made $1,500 worth of purchases, your utilization for that card is 15%.

Only the Equifax report shows the utilization information. You’ll find it on the first page under “Credit Accounts” where your debt-to-credit ratio — for each type of account and in total — is listed. To avoid a negative impact on your credit score, it’s wise to keep your use of “revolving” credit (such as credit cards) to less than 20% of available credit — not only for each card but overall.Length of Credit History

This accounts for 15% of your score. If closing an old account shortens your recorded credit history, that could negatively affect your score.

Closing an account also will affect your credit utilization percentage. For example, as noted above, if you typically charge $1,500 of purchases per month and your credit limit across all cards is $10,000, you’re utilizing 15% of your available credit. But if you close an account with a $5,000 limit and continue charging $1,500 each month, your utilization will suddenly become 30% ($1,500 divided by $5,000). To maintain a strong score, therefore, it’s generally better to not close old accounts.

Of course, there is an important exception to this general rule. For some people, having access to too much credit is a difficult-to-resist temptation, and reducing the amount of credit available would lessen that temptation. If that is the case, we suggest closing more-recent accounts while keeping the card with the longest history open.Types of Credit in Use

The FICO credit-scoring model looks positively at a “credit mix” — i.e., a combination of revolving credit (credit cards) and installment loans (auto loans, student loans). Your mix affects 10% of your score. Even so, don’t take out an installment loan just to try to raise your score. Improving your credit score is a worthwhile goal, but it’s not worth borrowing money unnecessarily to do so!New Credit

This impacts 10% of your score. Opening several lines of credit over a short period will weigh negatively on your credit score, at least temporarily.

Other information

In addition to listing the types of data described above, your credit report will identify companies that have reviewed your credit file recently. Numerous recent inquiries by companies to which you have applied for credit — known as “hard pulls” — can lower your score. (If you don’t recognize the organizations making such inquiries, that may be another indication of identity theft.)

Some types of inquiries won’t affect your score (so-called ”soft pulls”), such as when you request your credit report or when a prospective employer checks your report (which can be done only with your permission).

On your Equifax report, be sure to review these sections: “Accounts with negative information” (late payments), “Collections” (accounts turned over to a collection agency), and “Public Records” (bankruptcy, foreclosure). Any activity listed in these areas will definitely lower your score, so make sure there’s nothing there that shouldn’t be. By law, most negative marks on your credit report must be removed after seven years.

Stay away from companies that offer to fix errors or “repair” your credit for a fee. The Federal Trade Commission says such firms can’t do anything that you can’t do for yourself for free. Each credit report contains information about how to correct mistakes, along with details about what to do if you suspect identity theft.

Put a freeze on

If you’re concerned about preventing identity theft and want to block anyone from opening a credit account in your name, you can “freeze” your credit reports at no cost. This prevents lenders from accessing your reports, effectively stopping any new accounts from being opened until you unfreeze your reports. You can freeze accounts by going to these specific web pages for each of the three major reporting bureaus: