Just as there is “more than one way to skin a cat” (apologies to cat lovers), there is more than one way to manage one’s cash flow. Last month in this space, we highlighted four popular online money-management systems and touched on a few of the attributes of each. This month, we focus on the approach to budgeting that three of these systems (You Need a Budget, Every Dollar, and Tiller) have in common — namely, an emphasis on “zero-sum” budgeting. (Tiller can be set up to use either zero-sum budgeting or another approach.)

Conceptually, zero-sum budgeting is akin to the tried-and-true “envelope system” which involves placing predetermined amounts of cash into envelopes each pay period, using one envelope per spending category. At a supermarket, a purchase is made from the “groceries” envelope. At a clothing store, funds come from the “clothing” envelope. And so on. When money is spent, the user simply notes on the envelope the amount used and how much remains.

The envelope system still works, but times have changed. Most transactions these days — many of which are conducted online — are done by debit card, credit card, electronic transfers, or mobile payment services, rather than with cash. (Carrying around envelopes full of cash is also something of a security risk!) Still, the idea behind the envelope method — i.e., separating one’s money according to intended use and then deploying it accordingly — remains powerful.

Zeroing in on zero

A zero-sum budget is a means of making the envelope method function in a world of largely non-cash transactions. The key principle is to “give every dollar a job” — ahead of time. For example, a specific number of dollars will be assigned the collective task of paying your mortgage. The job of other dollars will be to buy groceries. Still other dollars will be enlisted for savings. Not a single dollar of income will be without a designated, predetermined task. (You Need a Budget applies the “every dollar” principle to all money at your disposal, including funds already in checking and savings accounts. Other systems apply the zero-sum approach only to monthly income.)

That said, most of today’s web- and app-based budgeting systems skip a helpful initial step in zero-sum budgeting, simply because they start with net income (the dollar amount received), rather than with gross income (what you are paid by your employer). In other words, most systems don’t account for 1) funds withheld from your paycheck for various taxes and (possibly) health insurance, or 2) your contributions to an employer-sponsored retirement plan.

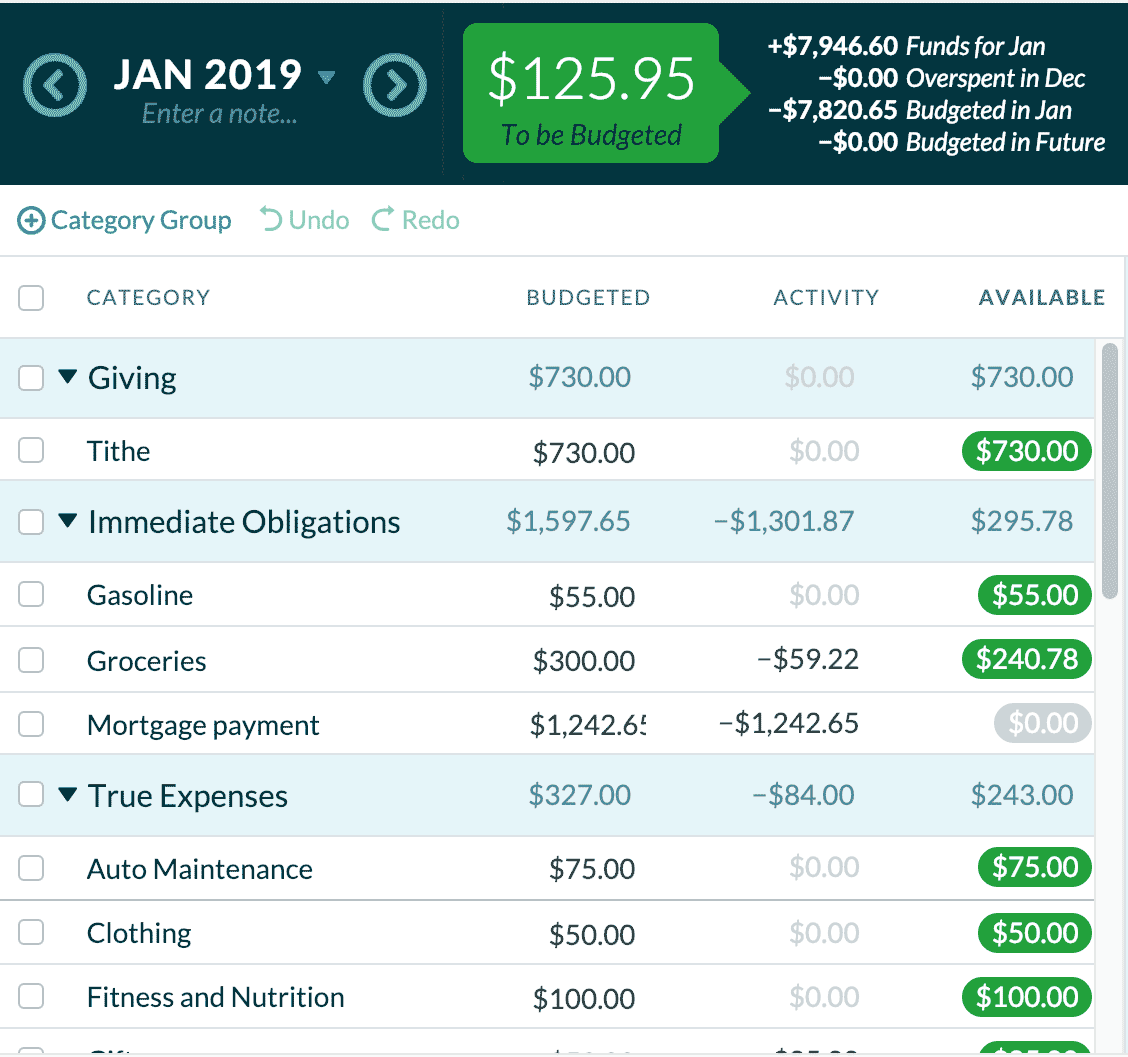

A portion of the You Need a Budget "dashboard."

There’s nothing wrong with managing a monthly budget based on your net pay — after all, that’s all you have to work with! But you’ll gain a clearer picture of where your salary goes if you begin with gross income.

From your gross pay, simply subtract the cost of the “jobs” assigned to each and every dollar. Let’s suppose, for example, that your gross monthly income is $6,000. If you tithe on your gross, begin by assigning $600 for your tithe. Then account for the total amount of tax-related withholding (you can find this figure on your pay stub), along with any amount you’re contributing to an employer-sponsored retirement plant.

In this example, let’s assume that what you have remaining at this point (after tithe, taxes, and retirement contribution) is $3,500. Continue to work toward zero as you give each dollar a job. Subtract $1,000 for a house payment, for instance, $350 for groceries, $300 for savings, etc. — using the dollar amounts that fit your situation.

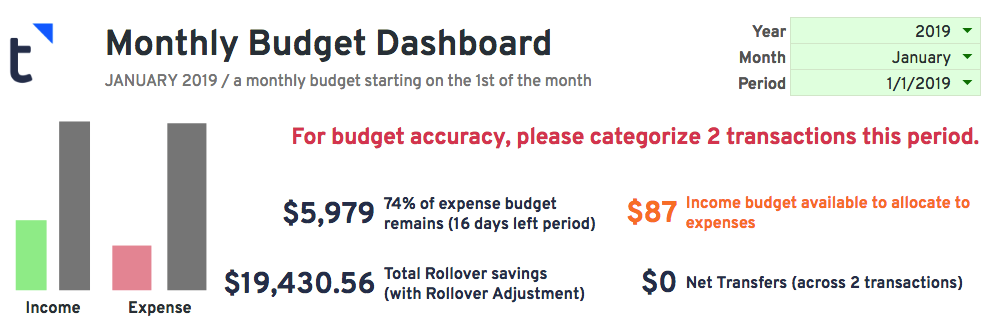

The “bottom line” goal of this planning process is to reach zero — i.e., for your outgo to equal your income — with all categories funded and nothing left over. If you haven’t given each dollar a job, you haven’t finished setting up your budget. You Need a Budget, EveryDollar, and Tiller will urge you to keep planning until every single dollar has a task. (Of course, if you have more tasks assigned than dollars to fulfill them, these systems will alert you to that fact as well.) Once every dollar has a job, your job is to follow through, making sure your dollars carry out the tasks you assigned in advance.

Of course, life happens. There will be months when you encounter unusual expenses, such as an automotive repair that exceeds the money you have on hand for that category. When that happens, you must shift money from other spending or savings categories, i.e., assigning some dollars to different jobs than originally intended.

On the other hand, if you end up with unused money in a category at the end of the month — let’s say you budgeted $100 for clothing expenses but spent only $75 — you have two options. You can “roll over” the remaining $25 to that same category for the following month (giving you a total of $125 for clothing expenses), or you can assign those 25 dollars a different job — such as helping to fund a savings goal.

A portion of the Tiller "dashboard," showing that 2 transactions

haven’t been categorized and $87 remains unallocated.

Periodic expenses

To be effective, of course, a budget must not only account for monthly expenses but also anticipate bills that come due only every so often. Auto insurance, for example, may be billed every six months. Life-insurance premiums typically are due every 12 months. The annual cost of Christmas gift-giving should be planned for as well.

In a zero-sum budget, you prepare for such periodic expenses by assigning some dollars future tasks. If your twice-a-year auto premium is $600, then $100 of your “monthly” money would be given the job of paying car insurance — but that money would “wait” (ideally by being transferred to a savings account or money-market fund) until the bill comes due.

Keeping things hands-on

One reason the old-fashioned envelope method works is that it is “hands on.” Each time you spend from an envelope, a reminder of your budgetary intentions and the evidence of your spending is literally in your hands, rather than simply being an entry in a computer.

Both EveryDollar and Tiller try to retain some of that hands-on sensibility by not automatically categorizing your spending transactions. By design, each system requires you to assign each transaction to a particular category yourself. You Need a Budget is similar in this regard — and for the same reasons — but it will auto-categorize repeating transactions, such as a mortgage payment.

Budgeting/tracking systems such as Mint are less rigorous than systems that use the zero-sum approach. Mint certainly can help you match expenses to income, but doesn’t go to the granular level of requiring you to give every dollar a job ahead of time.

A less-stringent system is fine for people who are disciplined enough — and have enough financial margin — that they don’t need to “sweat the details” required by the zero-sum budgeting approach. However, for people just starting out with a budget, or those still trying to control their spending and stop living paycheck-to-paycheck, the zero-sum approach may be just what is needed. Such an approach fosters careful planning, encourages regular interaction from the user, and helps assure that funds are available in each spending category, not only month-by-month but in the months and years to come.