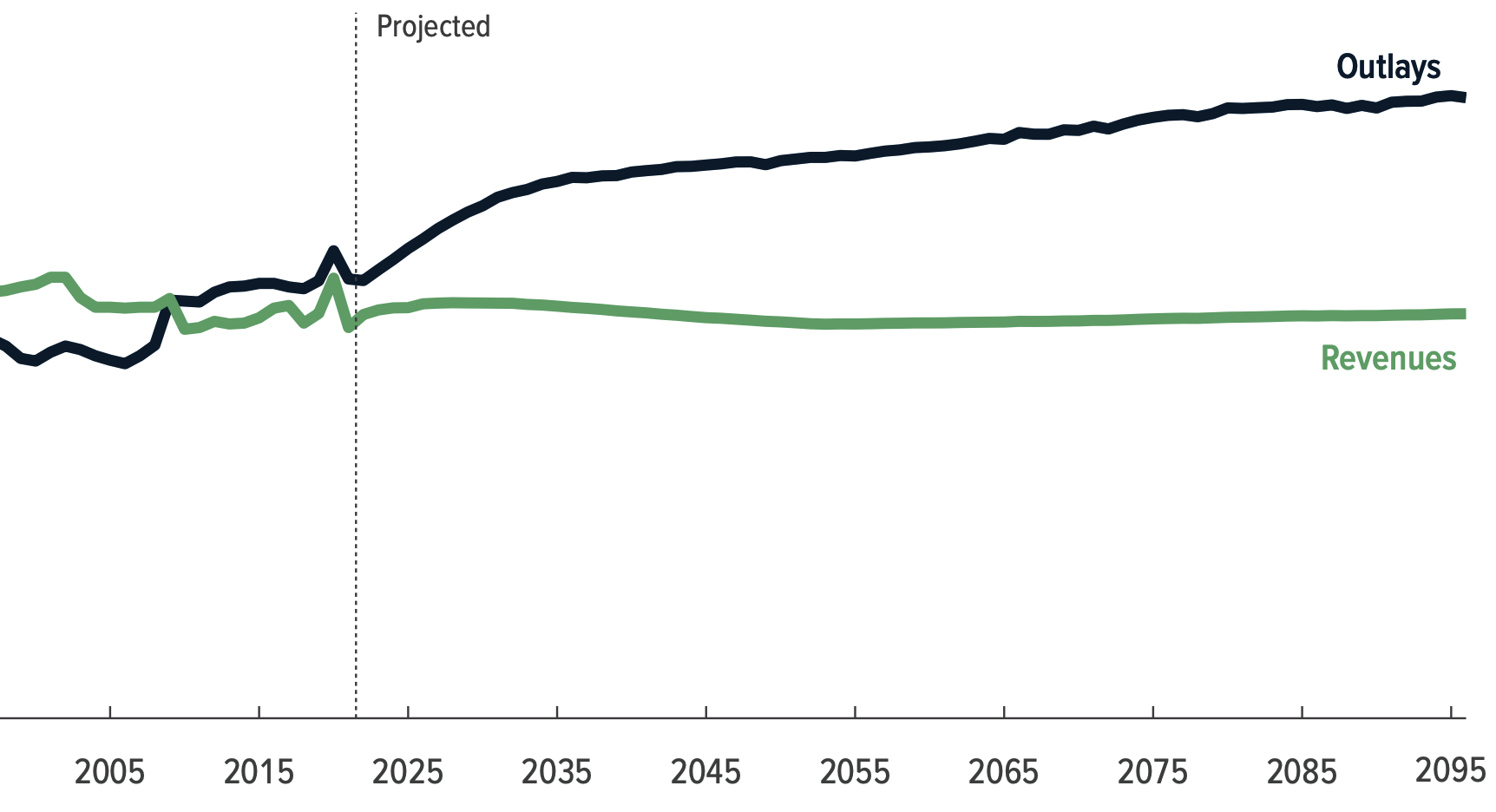

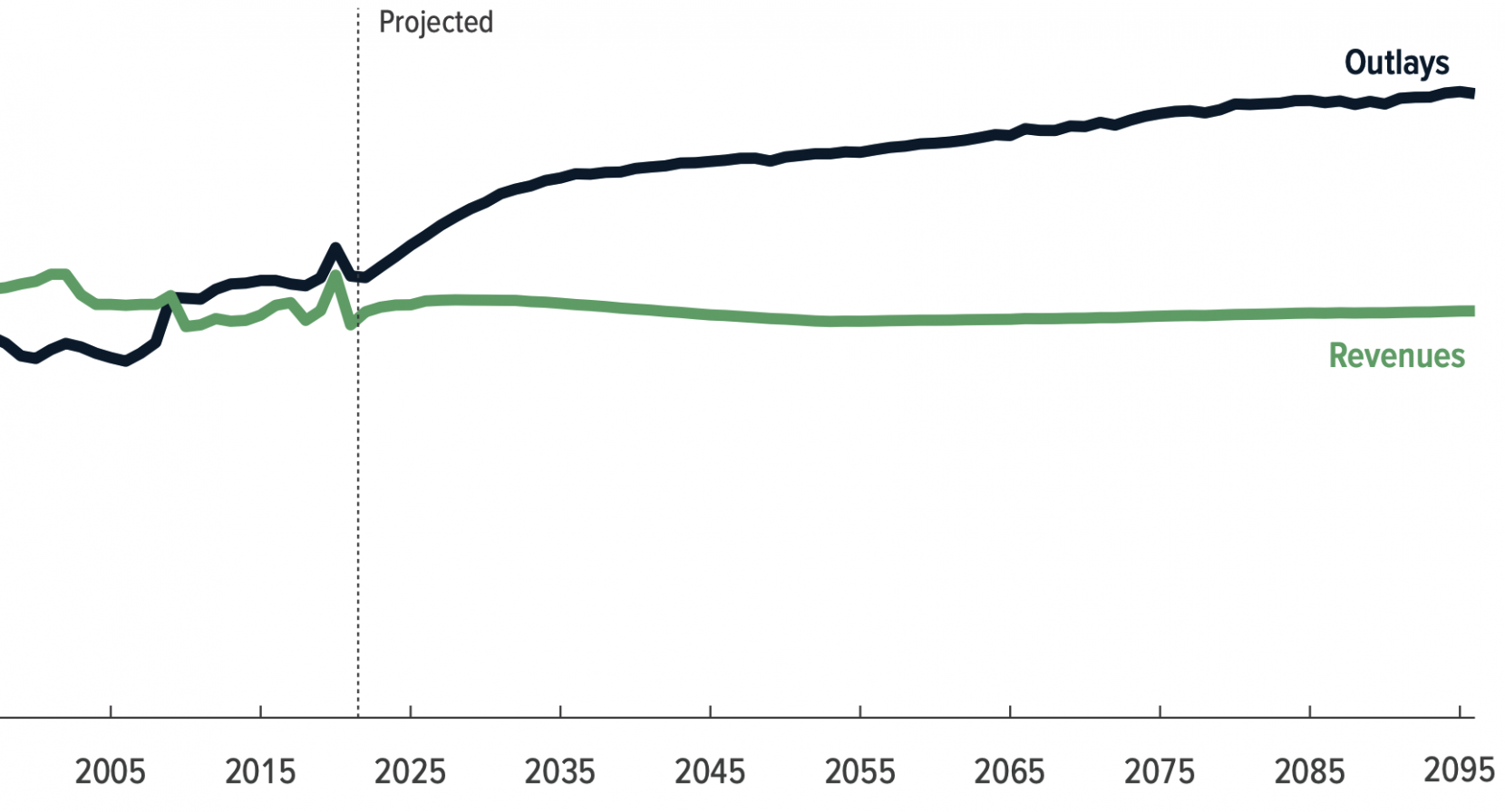

A new report on Social Security's financial situation isn't encouraging. You can see the gist of the problem in the graphic above.

Before presenting you with the details, here's a bit of history. Congress and the Roosevelt administration launched Social Security in the 1930s with three primary goals:

To assist lower-income workers who didn't have the financial wherewithal to set aside much money for retirement;

To help people who couldn't work anymore because of a disability; and

To provide for the survivors of workers who passed away.

Since then, subsequent Congresses and administrations have expanded Social Security benefits and eligibility to the point where the program's long-term math doesn't work (if it ever did). For the past dozen years, Social Security — the largest of all U.S. government programs — has paid more in benefits than it has received in revenues.

To cover the annual shortfalls, Social Security draws from its "trust funds," which hold bonds issued by the U.S. government. In other words, money from the government's general revenue pays off some of the bonds each year, thus providing enough additional funds for Social Security to pay promised benefits.

(It is worth noting that the government gets the money to pay those Social Security bonds by issuing more bonds — that is, by borrowing the money. This year alone, the government will borrow about $60 billion to pay off existing bonds held by Social Security.)

But the situation is deteriorating. The day isn't far off when all the trust fund bonds will be redeemed. That source of additional revenue for Social Security will go away.

And then — what?

According to a recent report (PDF) from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the combined trust funds for Social Security's Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance programs will be exhausted in 2033 — only a decade from now. (That's one year earlier than projected last year by the Social Security Board of Trustees.)

And then, according to the CBO...

...the Social Security Administration will no longer be able to pay full benefits when they are due (though beneficiaries will remain legally entitled to full benefits).

In the years after the trust funds' exhaustion, annual outlays would be limited to [the amount of] annual revenues, and payments to beneficiaries would need to be reduced (although the method for reducing payments is not prescribed under current law)....

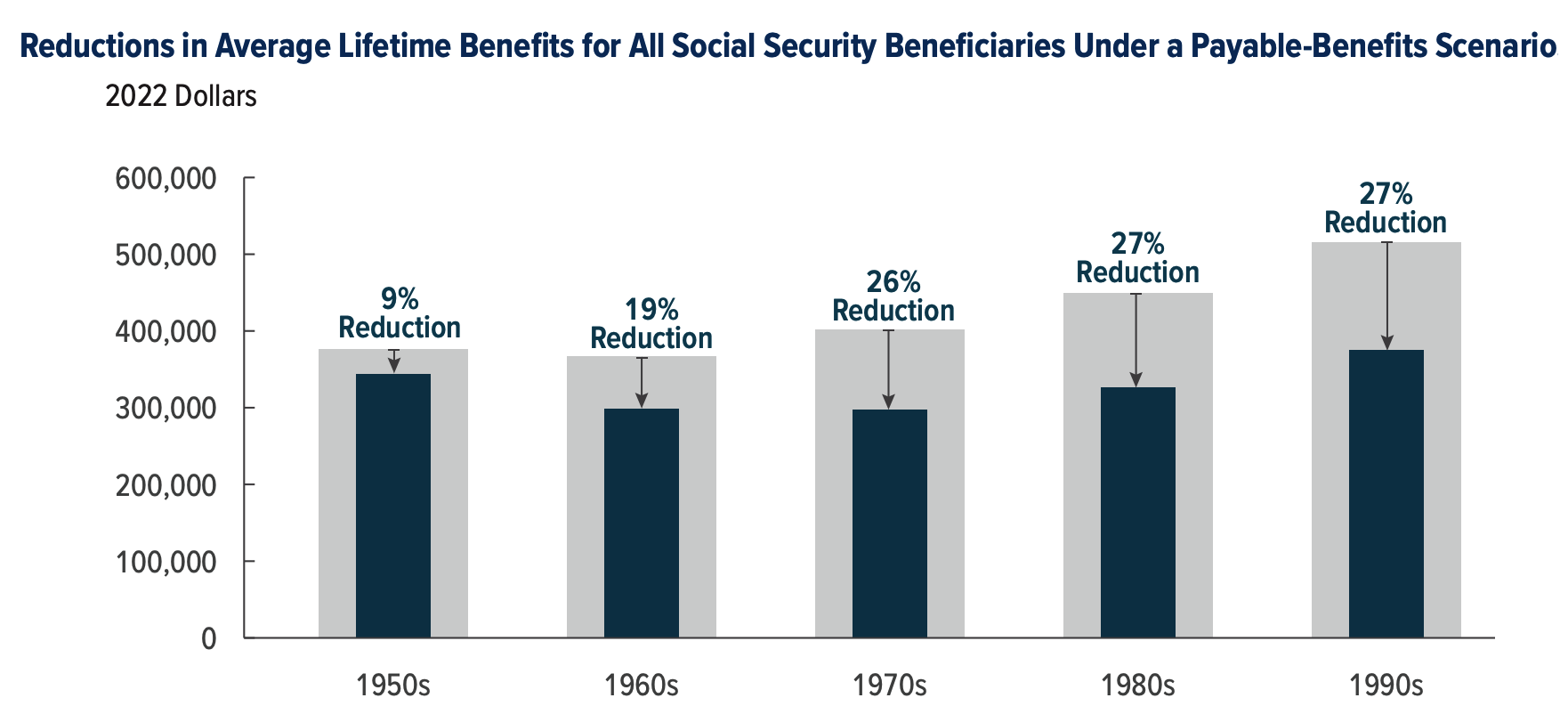

In 2034, Social Security revenues are projected to equal 77 percent of the program’s scheduled outlays, resulting in a 23 percent shortfall. Thus, CBO estimates that Social Security benefits would need to be reduced by 23 percent in 2034.

The Congressional Budget Office created this graphic to illustrate the lifetime impact of benefit reductions on workers born in different decades.

What's the answer?

Social Security presents a two-part predicament. There's the inescapable financial problem (outgo exceeds income) and the intractable political problem (voting to cut Social Security benefits and/or raise taxes is widely perceived as a political "death wish").

Is there an answer? Austin outlined the unappetizing possibilities in his October 2021 article, The Outrageous Truth About Social Security. Here are a few of them.

Changing the formula for calculating benefits

Modifying the annual Cost-of-Living Adjustment (COLA)

More means-testing

An increase in tax rates for both workers and employers

An increase in the tax on retiree benefits

Each option listed above is politically unpopular, and any solution likely would involve implementing several of them. That means upsetting multiple constituencies, and Congress isn't exactly known for its political courage.

Think you can craft a solution? Check out this (slightly dated) online tool created by a non-governmental group called the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

Bear in mind that addressing the financial problem is one thing. Making a solution for Social Security politically palatable is quite another.