Joseph did a great job on Monday unpacking the rapidly evolving lay of the land for savers in Cash? It’s No Longer Trash. After a dozen years of earning very little in savings products, it's refreshing to actually have some decent options again!

Today, I want to follow up on that discussion by looking at why someone might choose cash options (like CDs and money market accounts/funds) that have very little or no chance of loss, vs. the type of short-term bonds that we currently utilize as "cash" within Dynamic Asset Allocation. This also applies to those looking at our Bond Upgrading holdings and thinking, "Why own these short-term bond funds when I could just buy the Treasuries (or money-market funds) that Joseph discussed on Monday?"

Fixed vs. total returns

First, I should make a distinction between savers and investors for this conversation. For savers investing their emergency fund, access to that cash (liquidity) is first and foremost. That convenience factor is why local banks pay so little on their savings accounts — they know relatively few will go to the trouble of actually moving that somewhere else to earn a higher yield. But as Joseph discussed on Monday, it's really easy to do that, even if it's just to another online savings account. A few minutes spent setting up the new online savings account and linking it to your local bank account online can pay off significantly.

For investors, it's a little trickier, in part because they're often investing cash within a brokerage account. They may already think they're getting a good money-market rate, which Joseph explained is often not the case, as many brokers use "sweep" accounts that pay relatively little. This is where buying one of the better money-market funds (MMF) or Treasury bills, as he described in that article, can come into play.

The big advantage of buying a Treasury bond directly is you know exactly what the return will be over the time you own it. For example, a 12-month Treasury Bill is yielding 4.28% right now, so buying one today locks in your return for the next year. Easy and safe. Why would someone fool with a fund like SHY, which is 1-3 year Treasury Bonds, yielding a very similar rate today, when there's the potential downside that its return could fall due to rising interest rates (as has been the case for much of 2022)?

To understand the reason, we have to drill into what comprises the return from a bond fund as opposed to an individual bond. The individual bond is easy — what you see is what you get, as long as you hold it to maturity. With a bond fund, including those like SHY that own such short-term bonds that we often label them as "cash" within the SMI strategies, there are two components to the fund's return: income and capital gain/loss.

When you buy a bond fund, you are buying the fund's current collection of bonds. Today, SHY's current collection of bonds is pretty similar yield-wise to the 12-month Treasury Bill, as the yield curve is very flat — meaning there isn't much difference in yield between 1-year, 2-year, 3-year (and so on) Treasuries. For the sake of simplicity, let's just say the yields are the same between the 12-month T-Bill and SHY today.

The wrinkle with bond funds as opposed to individual bonds is that the bond fund's total return will be impacted by future changes in interest rates, whereas an individual bond held to maturity will not.

This can either help or hurt the bond fund's total return. For example, the 2-year Treasury yield has soared from 0.78% at the beginning of 2022 to 4.30% today. As interest rates rise, bond prices fall. So the story of 2022 for bond funds has been that the relatively small amount of income they were generating early this year has been dwarfed by the capital losses caused by rising interest rates. The longer the maturity of the bonds, the worse this impact has been.

SMI's Bond Upgrading strategy has gotten this right and owned primarily very short-term bonds this year, which has helped it lose much less than the broad bond market. But we still have losses for the year, which is why the certainty of positive returns via MMFs or buying individual Treasuries is so appealing.

Direction of interest rates

However, it's important not to get caught up in the recency bias of our 2022 experience here. This "total return" component works both ways — just as rising interest rates have hurt bond fund returns so far in 2022, falling interest rates have the potential to boost those returns.

So the big question as we evaluate this today is what is the likely path for interest rates from here? This is where things get interesting, specifically as we evaluate short-term bonds vs. longer-term bonds.

Normally, when inflation and economic growth are both falling, the best place to be invested is in bonds. So the million-dollar question is whether we've clearly transitioned into that type of environment. To my eye, it's pretty clear that we either already have or are getting really close, but with headline inflation numbers remaining sticky high and bond yields continuing to tick upward, skepticism is certainly reasonable.

The growth side of this is pretty easy, as real U.S. GDP has declined the past two quarters already and virtually every measure of global growth continues to slow. The inflation side is where the debate remains, and this is keeping the Fed on its hiking path which is continuing to exert upward pressure on rates.

SMI has maintained that inflation was going to stay sticky high for longer than many expected. That expectation hasn't changed. But there's plenty of evidence suggesting that inflation has likely already peaked and the real question now is how quickly will it fall and at what level will it plateau. There's a big difference between believing inflation will continue to be a problem because it levels off at 4-5% (rather than falling to the Fed's 2% target) versus arguing that it will continue to actually increase from today's levels.

There are plenty of clues supporting the idea that peak inflation is already behind us.

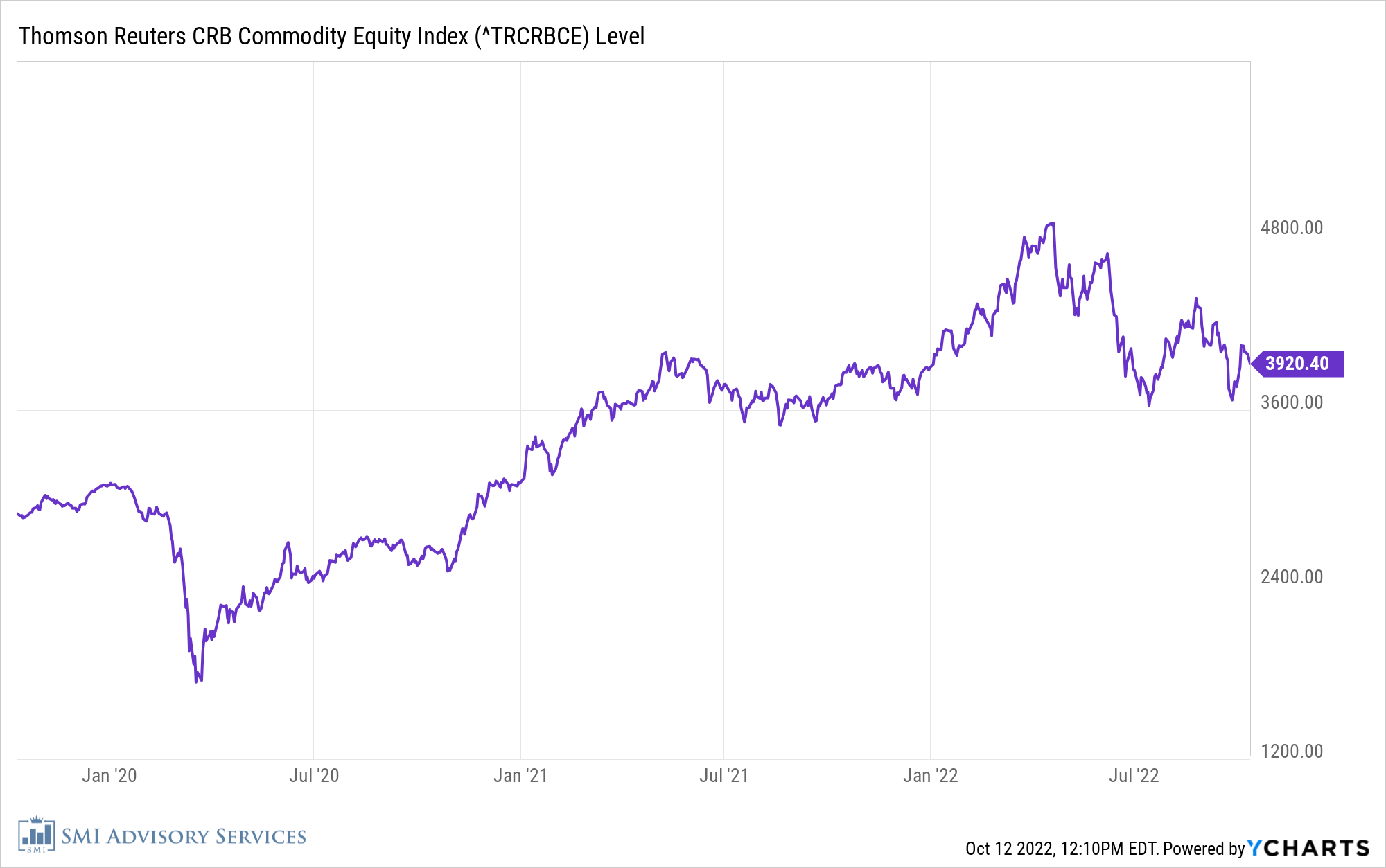

Here's a chart of the broad CRB commodity index. After rising steadily for two years, commodity prices peaked in April.

Click Graph to Enlarge

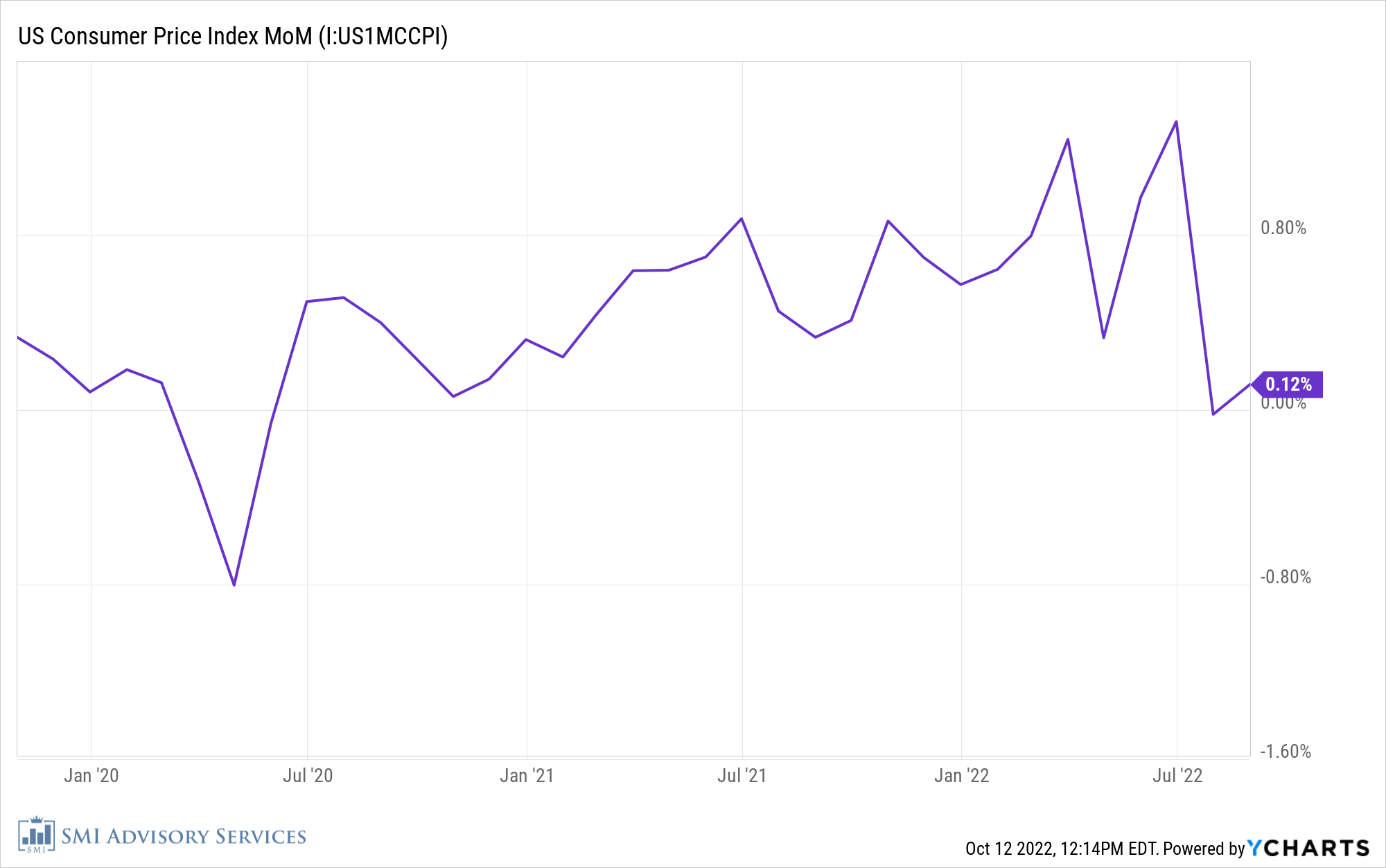

Here's a chart of monthly U.S. CPI. While this chart is a little noisy as the month-to-month varies, it helps show the declining momentum in recent inflation in a way that the headline annual number doesn't make as clear. (We'll see what tomorrow's new inflation data looks like!) While the one-month drop in April 2022 obscures the trend a bit, this chart follows the same pattern as the commodities chart above: rising steadily from March 2020 until peaking sometime in March-June of this year, then falling since then.

Click Graph to Enlarge

One final chart to make the point, here is monthly PPI — the Producer's Price Index — essentially the rate of inflation in prices manufacturers are seeing in the input costs of the goods being created. This is widely viewed as a precursor to CPI, as inflation tends to hit producers first (PPI) who then pass those costs along to consumers (CPI). Same trend here — rising into Spring 2022, peaking in March, and steadily declining since then, albeit to still "sticky high" levels.

Short-term rates are close to peaking

Long-term interest rates are set by bond investors based on many factors. Short-term interest rates (two years or less) are much more straightforward and heavily influenced by the Fed. Which makes it a little easier to speculate on the direction of short-term rates than long-term rates.

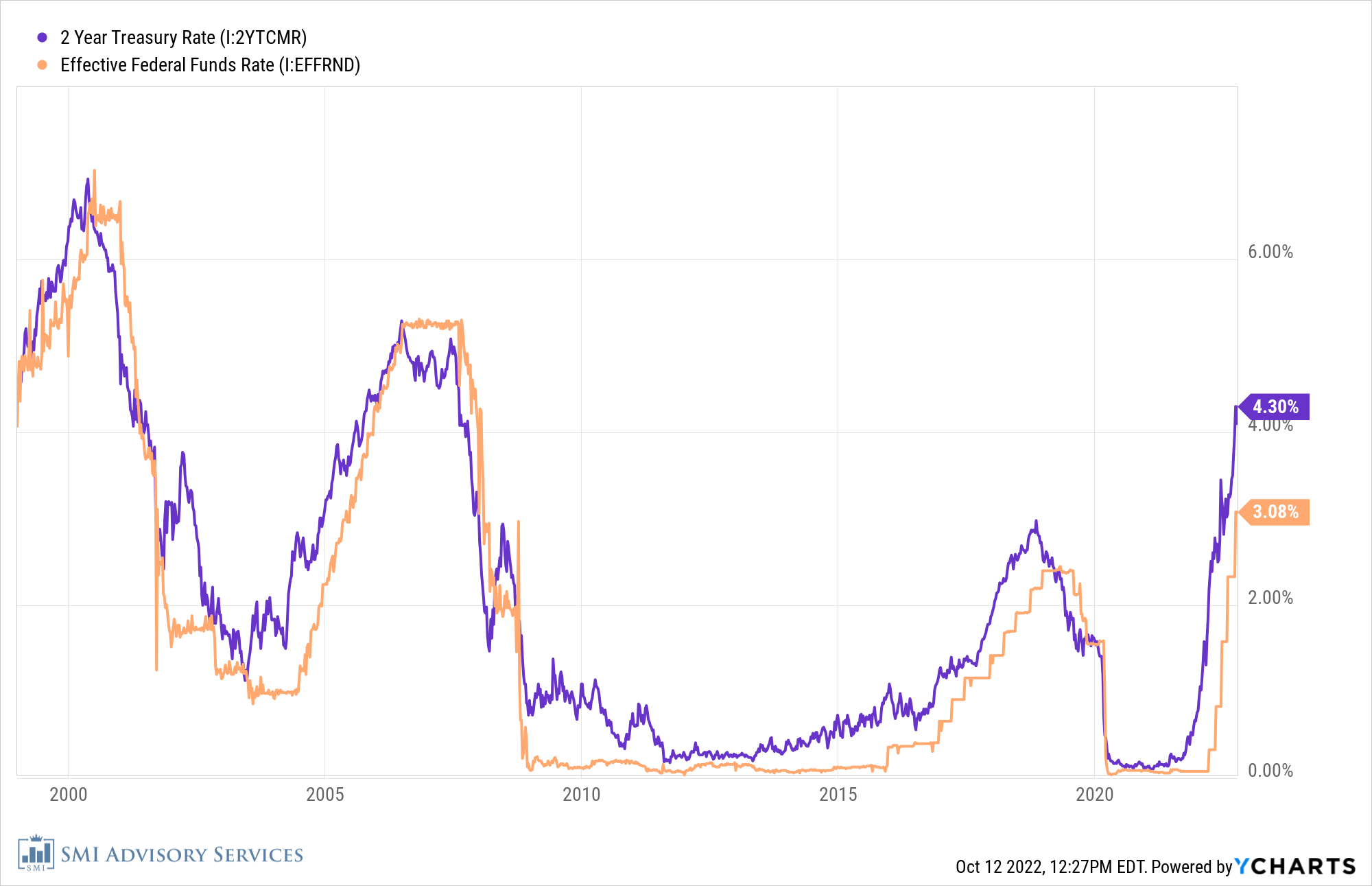

Here's a little secret you've probably never heard before. Rather than follow the Fed's interest rate policy decisions, short-term rates tend to lead the Fed. Consider the following chart of the 2-year Treasury yield relative to the Fed Funds rate:

Click Graph to Enlarge

The purple line is the 2-year Treasury yield, while the orange line is the Fed Funds rate. Note that the purple line (2-year Treasury) typically moves first, both higher and lower, while the orange line (Fed Funds) then follows. This is most obvious on the right side of the chart, from 2013-present.

This is the key to this whole article, so follow this point closely. The Fed is still hiking the Fed Fund rate in an effort to bring inflation down. But we've already likely seen the peak in inflation. Meanwhile, economic growth is clearly slowing. The Fed shot their "transitory" bullet last year and was proven horribly wrong, so they have no choice but to keep hiking now until the actual inflation numbers back down lower.

But look at the far right of this chart. The 2-year Treasury yield is 4.30% while the Fed Funds rate is 3.08%. The Fed has 1.22% of cushion to keep raising rates just to catch up with where the market is already pricing 2-year Treasuries. In other words, the Fed could hike 0.75% in November and another 0.50% in December and just be reaching the level where 2-year Treasuries are trading already.

In the face of a deteriorating economy, it's very reasonable to wonder whether short-term interest rates have already peaked — or, at a minimum, are very close to peaking.

SHY vs. MMFs or individual Treasury Bonds

If this view is correct, we're close to the point where short-term bond funds (including SHY, VCSH, VTIP, and BSV) will stop having rising rates subtract from their total returns and will instead start to see falling rates add to their returns. Remember, the chart shows that 2-year rates lead the Fed, so even if the Fed eventually pauses and holds the Fed Funds rate steady, it's likely the market will start to reduce the 2-year Treasury yield in anticipation of the eventual rate cuts that always accompany recessions.

All of this is to say that, from today's current rate level, short-term bonds look like a great risk/reward opportunity. It's hard to believe the Fed will continue to hike significantly higher than the 4.30% level the market has already priced in for the 2-year Treasury, while it's pretty easy to envision those short-term rates leveling off (and potentially falling) during the back half of this bear market, which is likely to be a recessionary period for the global economy.

That's why I continue to like short-term bond funds within the SMI strategies at this point. Granted, inflation and rate levels have both surprised to the upside this year. Taking the fixed rate via an MMF or buying individual Treasuries obviously provides a level of certainty that bond funds do not. But I expect the total return over the duration of this bear market will be higher via the recommended bond funds within the SMI strategies. (Plus they're easier to pivot from if the trend of lower rates eventually becomes firmly established and we want to move out into longer duration with a portion of our bond money.)

The misery of bonds so far in 2022 makes it easy to forget that bonds are usually the best place to be during periods of falling inflation and economic growth, which is the environment I expect to see over the next few quarters. Today's substantially higher yields present a much better "floor" for bond returns moving forward than the skimpy yields we had to start the year. That both cushions our risk as well as amplifying our potential upside should interest rates eventually turn lower.