As emergency measures designed to weather the COVID lockdown have morphed into seemingly permanent new policies, concerns over the potentially inflationary implications have skyrocketed.

If we have entered a new inflationary regime, there will be significant implications for the way investors construct their portfolios. We examine the current inflation evidence and discuss how investors can protect themselves from this emerging threat.

One common definition of inflation is “too much money chasing too few goods.” As simple as it sounds, that insightful phrase is particularly helpful as investors try to sort out the most important investing question of the day — are we in a new inflationary cycle?

The answer isn’t as straightforward as you might think. During the last period of significant persistent inflation in the 1970s, Nobel prize-winning economist Milton Friedman famously noted, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

By this standard, we should certainly be wary of rising inflation today, as we’ve never seen developed nations increase their money supply at the rates witnessed over the past year. Jeremy Siegel, a professor of finance at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, noted recently in the Financial Times that last year’s 24% surge in U.S. M2 money supply was the largest increase in the 150 years of available data. U.S. fiscal stimulus is running in the neighborhood of $6 trillion over the past year, roughly one-quarter of U.S. Gross Domestic Product (the total annual output of the U.S. economy). And while this initially appeared to be emergency spending to get us through an unprecedented economic crisis, it has become obvious there is no plan to stop the extraordinary spending now that the economy is healing. Debate has already begun over $3 trillion more in so-called “infrastructure” spending to be voted on later this year.

However, there’s one fly in the inflation ointment. Most of the same voices sounding the alarm for higher inflation today were doing the same thing a decade ago as we emerged from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Then, as now, we had huge increases in debt, spending, and new stimulus in the form of central bank-driven Quantitative Easing. Yet the anticipated inflation never materialized. Instead, the past decade became one of the lowest growth, lowest inflation periods on record.

Two big lessons stand out from the experience of the past decade. First, Friedman’s inflation assertion rests on an important assumption that was true in his day but hasn’t been in recent years. That is, for an increase in the money supply to translate into higher inflation, the velocity of money needs to stay relatively constant (or increase). This simply means that people need to keep spending at the same rate as before so the speed at which dollars circulate in the economy is either staying flat or accelerating. When the velocity of money is high, each dollar is moving fast to purchase goods and services. However, this didn’t happen in the aftermath of the GFC. Instead, the velocity of money slowed down dramatically. Increasing money supply but decreasing velocity caused those factors to largely offset each other, resulting in no increase in inflation, contrary to widespread expectations.

The second lesson from the past dozen years is that Quantitative Easing policies by the Federal Reserve and other global central banks are not inflationary in and of themselves. These QE policies, in simplest terms, describe how central banks, which have the power to create money essentially out of thin air, use it to buy assets from banks, usually Treasuries, thereby injecting money into the financial system. These assets are then added to the central bank’s balance sheet.

Based on Friedman’s formula, most people expected this to be inflationary, as it appears to push more money into the economy. But experience has shown that much of this simply stays on bank balance sheets because the banks do not always lend it out. This could become inflationary if it resulted in an increase in lending, getting those dollars circulating and boosting velocity. But that hasn’t happened and doesn’t appear likely given the huge debt levels already present in society and the general lack of demand for additional lending.

All of which leads us back to today’s conundrum. On the one hand, we see inflationary signals like the exploding money supply and significant changes to how government support is being administered to the economy. And we certainly are seeing early signs of inflation percolating throughout the economy. But on the other hand, we have the experience of the past decade — and really the past four decades of consistent disinflation (lower rates of still-positive inflation). This experience whispers in our ear to be careful about getting too hyped up about the inflation threat.

While we likely won’t conclusively settle this issue for you with this article, our study of the subject has led us to some important conclusions. Most importantly, we aim to explain how the potential of rising inflation relates to your portfolio, and how SMI’s strategies can — and to a significant degree, already are — defending against this potential risk.

Transitory reflation vs. sustained inflation

SMI has had an eye on this inflation possibility for many months already. Over the past year, we’ve written about multiple inflation-related topics: gold, the dollar, commodities, IVOL, and so on. So it may be surprising we aren’t more emphatically in the inflation camp.

To be clear, inflation is rising already. It’s no longer a hypothetical “it may rise in the future” situation. Of the many examples we could point to, the most attention-grabbing so far was the 4% monthly increase in March for “Processed Goods for Intermediate Demand.” These are inputs that feed into other goods, things like steel, chemicals, and plastics. This was the largest monthly increase since 1974!

This is exactly the type of evidence that causes many (including us) to expect significantly higher inflation in the months ahead. So to our eye, the question isn’t whether we’ll have higher inflation or not. It’s whether that higher inflation will persist, or if it’s “transitory” (to borrow the favorite phrase of current Federal Reserve Chairman, Jerome Powell). Let’s briefly examine each case.

Transitory reflation.

The economic data, along with real-world businesses and supply chains, have been thrown a massive curveball by the events of the past year. On the data front, making sense out of numbers that span the first-ever globally-coordinated economic shutdown and subsequent re-opening is challenging, to say the least. Today’s economic growth data looks amazing, but compared to what? A year ago, when the whole world was shut down? Last month or last quarter? It’s hard to glean insight from the crazy plunge/recovery nature of virtually every figure.

On the business and supply chain side, many industries have been massively disrupted by various shortages. This has led to crazy price spikes in products spanning a diverse range of industries: cars, wood products, even ketchup. These supply chain disruptions cause higher prices but aren’t necessarily “inflation” in a traditional or lasting sense. While there is a legitimate case to be made that the world has passed “peak globalization” and supply chains will become increasingly regionalized, which would potentially be an inflationary factor in the future, most of today’s supply chain driven examples of higher prices are expected to be relatively short-lived and dissipate as economies fully re-open and normal supply chains are restored.

This transitory idea is being promoted by Jerome Powell and other global central bankers. Ironically, these folks have done everything in their power to manufacture inflation over the past dozen years, with little success. Now that we actually have some, they’re quick to explain why it won’t last!

Beyond these arguments, the most compelling reason to believe the current inflation spike may be short-lived is that the three most important factors driving the inflation rate lower over the past 40 years haven’t gone away, and have arguably even strengthened over the past year. Every developed country has added dramatically more debt, our aging demographics haven’t improved, and the role of technology in our lives has only increased as a result of COVID. These three factors — Debt, Demographics, and Technology — are strongly deflationary and have driven the trend of declining inflation for 40 years now. It will take an even stronger offsetting inflationary force to turn this disinflationary long-term trend into an inflationary one as we move beyond the initial re-opening/normalization phase of the economic recovery.A new inflationary regime.

What could be powerful enough to overpower the debt/demographics/tech deflationary combo? Enter the Federal Government! And not just the U.S. government, but the combined efforts of the governments and central banks of all the major world economies.

The inflation argument really begins with a recognition that governments have wanted inflation for some time now, and need it now more than ever. Why do they need it? Because our collective debt is so high that the only plausible way to deal with it is to partially inflate it away. Inflation is the friend of the debtor as it allows debts to be repaid with less valuable currency.

But again, this is not a new problem, nor is the effort to generate inflation new. As we’ve discussed, most observers expected the post-GFC Quantitative Easing policies to usher in a new inflationary era. But those efforts were largely thwarted by most of the new QE money getting trapped within the financial system as additional bank reserves, never making its way effectively into the real economy.

Today, we still have central banks engaged in QE, as well as continuing other “emergency measures” initiated last year such as direct purchases of bonds in the broader marketplace (bypassing the banks) despite roaring financial markets and a rapidly recovering economy.

But the significant change today relative to the past dozen years is that we’ve seen government fiscal policy engage in a way it hasn’t previously. The federal government, via COVID and continuing legislation, is now delivering huge amounts of money directly into the hands of consumers who spend it (rather than it winding up as reserves on a bank balance sheet). It’s plausible that this joining of monetary and fiscal policy has finally produced conditions that will get the velocity of money moving higher and spur inflation.

Bond market casts a skeptical eye on future inflation

It’s possible that this significant shift will cause inflation to rise in a sustainable way beyond this initial re-opening inflation bump. But we thought that a decade ago as well. New crisis, new response...different result?

The burden of proof is on the inflation camp to show that the disinflationary forces of the past 40 years have been overcome by a new inflationary regime. While ample signs of price inflation are showing up, there is one glaring source of evidence pointing the other way — the bond market.

If persisting, resurgent inflation was an obvious future outcome, we would expect the bond market — the largest, most inflation-sensitive market in the world — to react strongly to that threat. But it’s not. That’s true despite longer-term Treasury bonds slipping into their first bear market in 40 years during the first quarter of this year.

This brings us back to whether we’re seeing a change in the inflation trend, or simply growth-driven, short-term reflation after the economic disruptions of the past year. The bond market is the world’s most sophisticated inflation watchdog. Treasury bonds did see a massive spike in yields during the first quarter of this year. But in spiking from 0.93% at the beginning of the year to a high around 1.75% at the end of the quarter, the 10-year Treasury yield only rose back to roughly the level it was at pre-COVID. A year prior to that, in the first quarter of 2019, the 10-year Treasury Bond yielded 2.50%-2.75%, a full percent higher than today. And it’s worth noting the 10-year yield quickly fell back to 1.56% in April after spiking to its 1.75% March high. Is it realistic to believe global bond traders are willing to lock in 1.56% annual interest for the next 10 years if inflation is obviously going higher?

The TIPS market (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities), which builds inflation protection into its bond pricing, offers another clue as to the bond market’s inflation expectations. There, shorter-term inflation expectations have picked up modestly, while longer-term inflation expectations remain muted. In other words, similar expectations as the “transitory” camp: higher inflation in the immediate future, but receding back to the prior disinflationary trend.

Verdict: to be determined

The reality is the future path of inflation simply isn’t knowable at this point. There are eloquent proponents in both camps, and both offer compelling arguments. But until the data confirms one path or the other, there’s no way to know for sure who will be right. Perhaps even more importantly, decisions by various actors (like Congress and the Fed) that have yet to be made will likely play a role in determining the future path of inflation.

So while we’re not yet ready to place all our eggs in either basket, we’re watching closely. The current inflation data is mixed — there are clear signs showing up in places like commodities and the economic data itself, yet the bond market’s response remains muted. But there is one factor that could ultimately override all others: the powers that be want inflation very badly. Unpayable debt tends only to be resolved in three ways: default, revolution, or inflation. Given the options, it’s easy to see why governments are angling to produce inflation, as it’s the only palatable path out of the debt wilderness they’ve led us into.

Given that, it’s reasonable to recast the events of the past dozen years in a different light. That is, central bankers tried QE after the financial crisis thinking it would boost economic growth and inflation. Having seen that it did neither, they’ve made that “emergency policy” permanent while adding to it new government-driven fiscal policy (as seen in Congress’ massive increases in federal government spending) in pursuit of the same growth/inflation goals. And if this combination of policy responses doesn’t produce the intended result, they’ll likely keep trying more new ideas until they eventually figure out how to generate the inflation they need. Ultimately, this might be the most compelling reason to expect an eventual inflationary outcome.

Investing implications of rising inflation

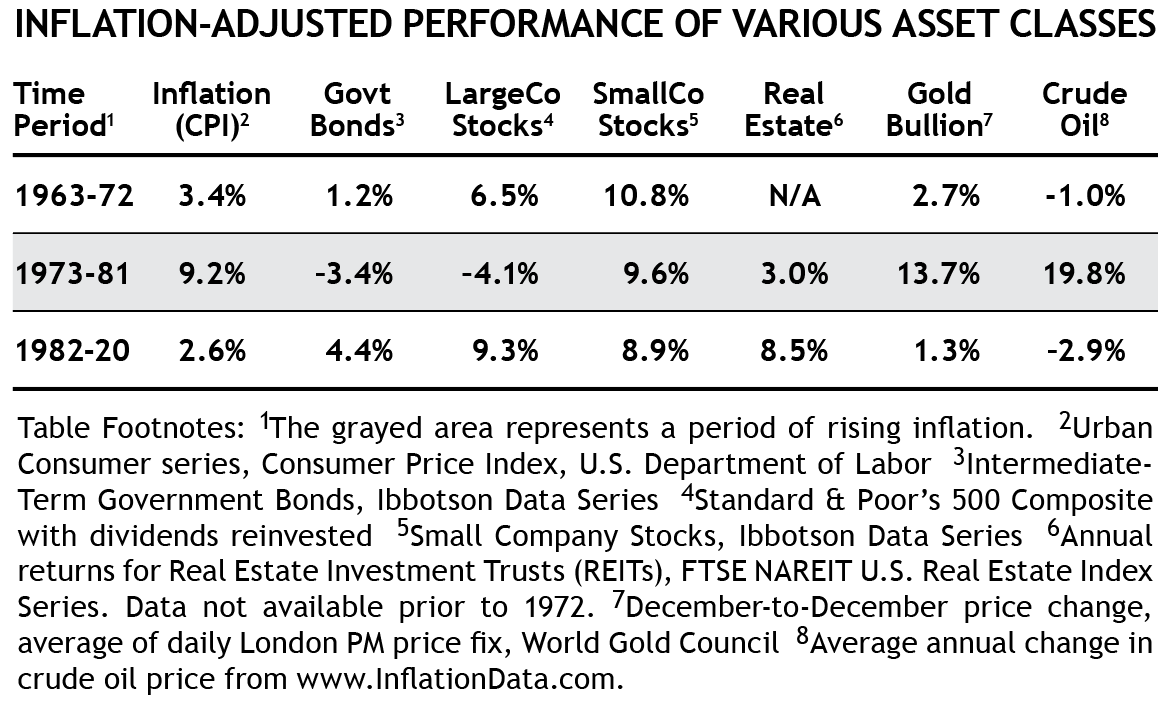

Let’s briefly review the historical perspective regarding investing during inflationary periods. As the table on the next page shows, there is only one relatively short period out of the past six decades to study, so we have to be careful about drawing sweeping conclusions from a sample size of one. But there are important clues to be gleaned.

The table below shows the inflation-adjusted returns from various investment classes, both in the pre- and post-periods of lower inflation, as well as the 1973-81 inflationary period.

The numbers are calculated by taking the reported returns (the “nominal” data) and adjusting for inflation (arriving at the “real” returns). Investment performance during an inflationary period often looks acceptable on the surface, but the inflation-adjusted data reveals there was actually little growth, just a re-pricing to keep pace with inflation. For example, consider the -4.1% return of large-company stocks during the 1973-81 inflationary period. The nominal gains were +5.1% per year, which doesn’t sound too bad. Only after reducing those nominal gains by the 9.2% rate of inflation do we see large company stocks actually lost purchasing power at a rate of -4.1% per year during that period. The reported “gains” were largely an illusion.

Click Table to Enlarge

Let’s take a closer look at each of these key asset classes and see what role they might play in combating the effects of inflation, as well as how the SMI strategies handle each one.

Bonds

There’s no question bonds are the most obvious pain point if we’ve entered into a new inflationary environment. While the 1973-81 returns weren’t terrible, keep in mind interest rates were much higher then, which meant more income to cushion the blow of falling bond prices. We don’t have to look further than the first quarter of this year to see how painful higher rates can be for owners of longer-term bonds. Vanguard’s long-term bond index fell -10.0% in the first three months of this year. (Investors who buy and hold individual bonds until they mature aren’t affected by such price swings.)

Thankfully, SMI has been proactively preparing for this long in advance. The creation of our Dynamic Asset Allocation strategy in 2013 resulted from research done specifically to try to figure out how to build portfolios that were less reliant on the large, semi-permanent bond allocations that asset managers have gravitated to in recent decades. As a result of that defensive breakthrough, SMI was already reducing the static percentage most members allocate to bonds.

Similarly, we redesigned our Bond Upgrading approach to better protect against the risk of higher interest rates. That strategy includes inflation fighters like TIPS, opportunistic plays like Reams Unconstrained Bond, and the IVOL product we reviewed in the March article, IVOL: Profiting From Rising Interest Rates.

The most obvious thing bond investors can do to reduce inflation risk is to shorten the maturities of the bonds they hold, which Upgrading has done over the last year. But these other specific tools can help as well.Common Stocks

Relatively low rates of inflation aren’t typically harmful to stock prices, as businesses can generally pass along higher costs to consumers in the form of higher prices. However, when inflation rises to 1973-81 levels, it becomes harmful to the overall economy. In that event, stocks and stock funds can be negatively affected. Index funds will likely do little more than keep pace with inflation in this environment. As always though, some fund managers will do better navigating those waters than others, and those funds will rise in our fund- momentum rankings. In addition to the normal momentum-driven process, Stock Upgrading was refined at the beginning of 2021 to allow it to lean more strongly in the direction of value stocks (where many of the more inflation-resistant companies reside) over growth stocks. This should be a significant boost if higher inflation is more than transitory.Real Estate

An intuitive move in times of high inflation is to own tangible assets. Normally, the value of such assets would be expected to rise to keep pace with inflation. Home prices are a good illustration of this, as many American homeowners have watched the prices of their homes rise dramatically over the past several decades, pushed ever higher by the relentless march of inflation. Naturally, there have been periods when home prices have risen faster than inflation and then corrected, but for the most part, owning a home has been a good hedge against inflation, particularly when purchased via a mortgage that was repaid with ever-cheaper dollars over a long period of time.

While owning a home has been a good inflation hedge and a form of inflation-protected “forced savings” for many, moving beyond homeownership to investing in real estate is quite a bit more difficult. Rental properties offer some of the same inflation-protection benefits, but are extremely high-maintenance investments, making them poorly suited for many investors.

The most accessible way for most investors to participate in real estate has traditionally been through REITs (real estate investment trusts). REITs typically own income-producing commercial real estate, such as apartments, office buildings, shopping centers, and so forth. REITs can benefit from inflation, as their financing costs and other expenses tend to stay steady while the value of their underlying properties increases along with the rents they are able to charge. However, much as with stocks, while a little inflation is good for REITs, a lot of inflation is not. When inflation begins to drag the overall economy into recession, commercial properties get hurt. Vacancies rise, less income is produced, and this is reflected in the returns from REITs. Still, REITs can be a good diversifier for a stock portfolio and can help combat the type of relatively modest inflation most envision even under the “persisting higher inflation” type of regime we’ve discussed in this article. DAA monitors REITs and tells us when they are compelling to own and when to avoid them.Gold

Much of gold’s reputation as an inflation fighter stems from its outstanding performance during the 1973-81 period highlighted in the table. But that could be a bit misleading as gold’s price was largely fixed until 1971. Still, gold has served as a good store of value over the long term. Adjusted for inflation, a dollar invested in gold at the beginning of the 19th century has been worth roughly a dollar ever since. There have been highs and lows along the way, but what’s rather remarkable is the consistency with which gold has stayed at roughly the same inflation-adjusted value. Gold is included in DAA’s asset mix to give that strategy plenty of inflation-fighting power.Commodities/Oil

Oil and other commodities are some of the purer inflation-oriented investments available. Simply put, as prices rise throughout the economy, the cost for the raw inputs of economic growth goes up.

This doesn’t necessarily happen in a linear fashion, as the mere expectation of future increases can front-load the increasing price effect of oil and other commodities. (This can also happen in reverse, causing prices to decline before inflation has actually abated.) While high inflation does eventually cause demand for industrial commodities to drop as the economy slows, oil and other commodities have still done much better than most other types of investments at not only keeping pace with inflation but actually producing significant real returns. We’ve seen huge moves higher in commodity prices over the past year, partially reflecting the supply disruptions discussed earlier, but also potentially in anticipation of future inflation. Commodities are included in SMI’s Upgrading strategy, and we also have seen Sector Rotation perform extremely well during past periods of rising commodity/oil prices.

Transitory or sustained, SMI is prepared

If you’ve ever stood in the ocean as the waves washed the sand out from beneath your feet, you have insight into the insidious nature of inflation. The value of our dollars is being steadily eroded. Sometimes the waves come in faster and stronger, other times more slowly. Today’s rapidly expanding fiscal stimulus threatens to speed up the rate at which our dollars lose their value. That’s a significant risk that would require a different investing mix than investors have grown accustomed to over the past 40 years.

Thankfully, it’s a risk we’re prepared to handle. With a little preparation and ongoing vigilance via the SMI strategies, you can reasonably hope to earn returns well in excess of inflation.