At first glance, the cost of investing in a mutual fund seems straightforward. The net asset value (NAV) is the price of each share. For example, the NAV of the Allianz International Small Cap fund (AOPAX) as of this writing is $45.44. That’s what one share costs.

But there’s more to the story. Of course, the company offering the fund has to get paid for its services, and it does so through one or more of the fees described below. To be an informed investor requires an understanding of the true cost of the funds you buy.

Expense ratios

A look at AOPAX’s prospectus reveals a “net expense ratio” of 1.25%. That indicates the total amount a shareholder will pay annually to help cover the fund’s overhead and profits. For every $1,000 invested in the fund, $12.50 will go toward the fund’s management each year. (You may also see a higher gross expense ratio listed, but it’s the net expense ratio that affects you. Any added costs included in the gross expense ratio are waived or reimbursed to investors.)

Costs covered by a fund’s expense ratio include operating/management expenses and marketing expenses.

Operating/management Expenses

All funds cover their operating expenses out of the money shareholders invest. The largest such expense is typically the fund’s “management fee,” which pays the salaries of the portfolio managers and any supporting staff (financial analysts, etc.). Other operating expenses include the costs of having an office and equipment, additional staff, and the fees paid to a bank to maintain shareholder accounts and safeguard all the money and securities constantly coming and going. There are also the costs of presenting regular reports to shareholders, and obtaining legal and auditing services. Finally, after all the above are paid for, any remaining money constitutes the fund’s profits.Marketing Expenses

Many funds pay their marketing expenses out of the management fees they collect. Others, including AOPAX, add a separate item called a 12b-1 fee, named after the SEC ruling that permits it. This money is used to promote the fund to prospective investors, typically by paying distribution fees to brokers. Schwab, for example, charges a fund 0.40% of its assets annually for the fund to be listed as a “no-transaction-fee” offering on Schwab’s platform. It’s not difficult to understand why some funds recoup a portion of those costs by adding a 12b-1 fee. (The maximum allowed for a no-load fund is 0.25%.)

Even though a fund’s 12b-1 fees may be listed separately on a prospectus, all of the operating/management and marketing expenses (including any 12b-1 fee) are included in a fund’s stated expense ratio. These expenses aren’t paid all at once. Rather, in a manner invisible to the shareholder, a small portion is subtracted daily from the fund’s net asset value. The NAV a fund reports each day has already had that day’s share of the annual costs deducted. (As a result, SMI’s momentum scores already take into account the impact of each fund’s expenses.)

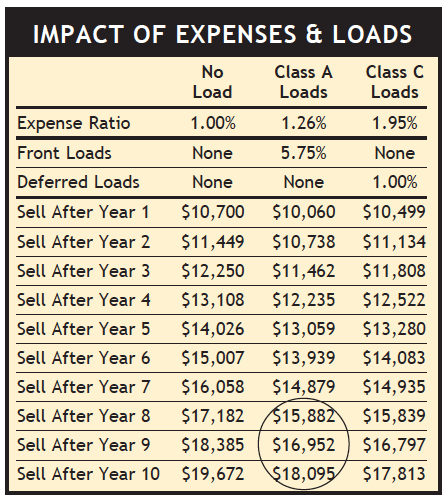

Assume a fund would have returned +8% each year if no expenses were taken out. In the table below, the first column shows a no-load fund that charges, as all funds do, an expense ratio. If there were no fees whatsoever, a $10,000 investment that earns 8% would be worth $10,800 after one year. However, since the fund charged 1% to cover its operating/management expenses, the amount grew to $10,700 instead.

Remember, published returns are always reported after the expense ratio costs have been deducted, so this fund’s published return would be 7%, not 8%. This makes it easy for investors to simply compare the stated returns for one fund against another without having to make further adjustments for expenses.

Sales loads

So far, we’ve been looking at no-load funds — those that are sold without sales charges. No-load funds charge fees to cover their costs, such as those expressed as an expense ratio, but they don’t make investors pay a sales commission.

No-load funds deal directly with investors without having a sales force represent them. They count on investors doing their own research and paperwork (or relying on a trustworthy investment newsletter for recommendations as to which funds to buy and sell!) and, therefore, not needing a broker to recommend which funds to buy.

In contrast, some brokers and financial planners get paid for their advice by earning commissions from the funds they steer money into. Those charging a front-end load (a commission that is paid right away when you buy a fund) are most commonly called “Class A” funds. The second column shows how significant a drag such fees can be on returns.

“Class C” funds compensate brokers by charging higher expenses (some of which are returned to the broker as an ongoing quarterly fee) and a back-end sales charge — one that investors pay when they sell such a fund. At a glance, these funds seem almost like no-load funds. Their deferred load is typically a relatively small 1%, and usually only applies to redemptions made during the first year an investor owns the shares.

You can see that, under similar market conditions, C-shares start off with a significant advantage over A-shares, due to avoiding the upfront commission. The table reflects a common front-end load of 5.75% and typical expenses for each share class, revealing that C-shares are usually a better deal than A-shares for several years after purchase. Only if a fund is held many years does the A-share eventually become a better deal due to its lower annual expenses (see circled data in the table).

As the table shows, no-load funds have a tremendous cost advantage over load funds. It would take an exceptional load fund to overcome the structural overhang of its higher costs.

SMI’s Upgrading strategy has historically focused primarily on pure no-load funds (with only occasional C-share recommendations). Recently though, some A-share funds have become available without a load, and have been recommended as long as one or more of SMI’s recommended brokers offers them on a load-waived basis. For example, AOPAX normally charges a 5.5% front-end load, but that load is waived at some of SMI’s recommended brokers, including Fidelity.

Avoiding class confusion

Many mutual funds have multiple share classes available. These differing classes of the same fund are invested the same way, but are either sold differently (through a salesperson or not), or are designed for different groups of investors (individual investors vs. institutional investors). Each class may require a different minimum investment amount and will likely have a different expense ratio.

In addition to load funds, which typically come in at least A- and C-shares, many no-load fund companies also offer multiple classes of their funds, usually charging lower expenses to customers with larger sums to invest.

For example, Vanguard offers some of its funds in both “Investor” and “Admiral” share classes. The Vanguard 500 Index Fund (VFINX) Investor shares charge an expense ratio of .14% and require a minimum investment of $3,000. The Admiral shares of the same fund have a lower expense ratio of .04%, but require a minimum investment of $10,000. For institutional investors, Vanguard offers some funds with even lower expense ratios, but the minimum account balance requirements are much higher. Fidelity offers similar distinctions on some of its funds (typically index funds), labeling them “Investor,” “Advantage,” and “Institutional” share classes. Schwab offers only retail vs. institutional shares.

Transaction fees

Just because an investor avoids paying a commission doesn’t mean he or she will never have to pay to buy or sell a fund. Many brokerages charge transaction fees for some no-load funds. That’s why SMI indicates whether each recommended fund is NTF (no transaction fee) or not.

As if the share class/transaction fee discussions aren’t complex enough, some brokers offer both a transaction fee and no-transaction-fee version of the same fund! Typically this occurs when a fund offers a second share class with higher ongoing expenses (perhaps by adding a 12b-1 fee) that help offset the cost of making the share class available NTF. SMI calls attention to this when recommending a fund by footnoting it and listing the alternate ticker symbol. In general, the larger the sum of money you are investing and the longer you expect to keep it invested, the more it makes sense to pay the transaction fee in return for the lower expense ratio, and vice versa.

Short-term redemption fees

One final fee to look for is a fee some brokers and funds charge if you sell funds within a relatively short amount of time after buying them. With brokers, the fee, ironically enough, pertains to no-transaction-fee funds. Different brokers have different policies. Among our recommended brokers, Fidelity and Vanguard have the most generous policies, charging a short-term redemption fee only if you sell an NTF fund within 60 days of purchase. Schwab and E-Trade require a 90-day holding period, and TD Ameritrade has the most restrictive policy at 180 days. In each case, the fee is around $50.

On top of the short-term redemption fee brokers charge, some funds charge these fees as well, equating to a percentage of the money you have invested. For example, the Hodges Small Cap fund (HDPSX) charges a 1% fee if you sell within 30 days of purchase.

The short-term redemption fee policy of each recommended broker is listed on the Choose Your Broker page of the SMI website. The policy for each Fund Upgrading recommendation is listed on the Basic Strategies page of the newsletter (p106) and the Recommended Funds page of the SMI website.

Clearly, understanding the true costs of buying and owning a mutual fund requires looking beyond its NAV. While it’s smart to steer clear of the most obvious fees, such as front-end loads, it’s also important to make fund performance a higher priority than fee avoidance.