Since 2011, Social Security has been paying out more in benefits than it takes in from taxes. For now, other sources of money make up the shortfall.

But according to the latest report from the Social Security Board of Trustees, the program’s financial situation is deteriorating. About a dozen years from now, overall revenue won’t be enough to pay all of the retiree benefits people are expecting.

Sooner or later, Congress will have to raise taxes or reduce benefits — or, more likely, both. It’s wise to be prepared.

That there has not been a popular uprising against the U.S. Social Security system can only mean that most Americans don’t understand how Social Security works. But that lack of understanding isn’t surprising. After all, the Social Security program has been misrepresented to the American people from the beginning.

When George Orwell wrote his classic novel 1984, he coined the expressions “newspeak” and “doublethink.” The ruling government (“Big Brother”) used newspeak (deliberately ambiguous or misleading language) to make lies sound truthful. It employed doublethink concepts (two contradictory ideas presented as harmonious) to convey an appearance of virtue where there was none. Our own government has proven masterful at this approach to communication in the words used to promote the Social Security program.

From the founding of our country, most Americans believed that caring for the elderly was a matter between family members. While Christian charities, churches, and even state and local governments would often assist those with special needs, the basic responsibility remained with the individual and families. But in the 1930s, that changed. The Social Security Act of 1935 effectively transferred responsibility for the elderly from the individual/family to the larger society.

Although Social Security was sold to the American people as an “insurance” program, it is more accurate to say that it is now, and always has been, a welfare program. In other words, it is a system designed to transfer tax revenues from one group of people to another. You may not like to hear that (I was reluctant to accept it myself). But once you understand how the system is structured, the nature of Social Security as a transfer program becomes obvious.

If Social Security had been proposed as a “welfare” program, it wouldn’t have been so readily accepted by a public that believed in self-reliance. So the government employed “newspeak” and “doublethink” to make the program largely unobjectionable to the American people. Let’s look at how this was done — and continues to be done today.

Doublethink #1: We’re paying a tax, but we’re told we’re buying “insurance.”

When Social Security was established, it became morally acceptable — for the first time — for the U.S. government to tax one group of citizens for the sole purpose of giving money to another group of citizens. To disguise this fact, the government named the primary Social Security program “Old Age and Survivors Insurance.” (It’s now called “Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance.”)

After all, buying insurance is a prudent financial step every family should take, isn’t it? True insurance, however, involves making premium payments proportionate to the risk involved. That’s why insurance companies hire actuaries — to help them set premiums based on reasonable life expectancies. Social Security isn’t like insurance at all; what you pay in has little correlation to your ultimate benefits.

In his 1987 book, Beyond Our Means, former Wall Street Journal economics editor Alfred Malabre explained:

“Consider a worker who began paying into the system in 1937, when it was launched, and worked until 1982. If he had paid the maximum in Social Security taxes each of the 45 working years, his payments would have totaled $12,828. His benefits would have begun at $734 a month. If he were married, his wife would collect half of his benefit, or an additional $367 monthly, bringing their total first-year benefit to $13,217, or more than he had paid in the 45 years of employment.”

Malabre goes on to show that if this hypothetical couple lived out normal life expectancies, their lifetime benefits would amount to some $375,000! (How is this lavish generosity possible? We’ll take that up shortly.)

Doublethink #2: Benefit amounts can be lowered, but we’re told those benefits have been promised.

We have been led to believe that, upon retirement, our years of payments into Social Security give us specific entitlement rights — that is, the government is obligated to honor its commitments. Unfortunately, that is not the case. The government can change the program’s rules anytime it wants.

Just look at Social Security’s history. It used to be that any American who paid into the system could retire at age 65 with “full benefits.” In 1983, as part of a Social Security bailout plan, Congress raised the full-benefits age requirement on a graduated basis. Under the new rules, people born between 1943-1954 had to work until age 66 to get full benefits. That involved not merely waiting an additional year to collect but also an additional year of paying in. For those “1943-1954 people,” what had been promised for much of their working lives (full benefits at age 65) was changed at the stroke of a pen.

Is that fair or honorable? No, but it is legal. In 1960, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled (Flemming v. Nestor) that Congress can do whatever it wants with Social Security: “The Social Security program is in no sense a federally-administered insurance program under which each worker pays premiums over the years and acquires at retirement an indefeasible [guaranteed] right to receive for life a fixed monthly benefit irrespective of the conditions which Congress has chosen to impose from time to time (emphasis added).”

It’s worth noting that Justice Hugo Black dissented, writing in part, “I cannot believe that any private insurance company in America would be permitted to repudiate its matured contracts with its policyholders who have regularly paid all their premiums in reliance upon the good faith of the company.” The reason Justice Black’s argument didn’t win the day is that Social Security is a tax, not insurance.

Doublethink #3: Money is taken from us involuntarily, but we’re told we’re making “contributions.”

With Social Security, money is taken automatically out of our paychecks and called a contribution. (In fact, the letters FICA you may see on your pay stub stand for Federal Insurance Contributions Act.) But unlike voluntary payments into a private pension plan, there’s nothing “voluntary” about these “contributions.” Try to get the government to stop the withholding and see what happens. The simple fact is that Social Security is a tax.

For many years, Social Security distributed a booklet (Your Social Security) that contained this statement: “Nine out of 10 working people are earning protection for themselves and their families under the social security program” (emphasis added). The truth is that the individual worker was not and is not “earning” anything — certainly not in the same sense as one who invests in an IRA or other private pension plan. Rather, what nine out of 10 working people are doing is paying taxes, which are then given to persons who are no longer working.

Doublethink #4: The SS taxes we pay are spent immediately, but we’re told our money goes into a “trust fund.”

For most of us, the expression “trust fund” suggests that a sum of money is being accumulated and invested safely, thus growing in value as it awaits the time when it will be needed. A “trust fund” sounds secure, so it would be understandable if you thought in those terms when you hear that your money is going into the Social Security trust fund. That’s what you’re supposed to think.

But that’s not what is happening. The Social Security program doesn’t set aside any trust money for our future use — and it never has. In fact, it is accurate to say that Social Security has a lot in common with “Ponzi schemes.” In such a scheme, money coming in from new investors is used to pay “returns” to earlier investors.

Remember Alfred Malabre’s example of the people receiving huge sums in relation to what they put in? Their withholdings couldn’t possibly have grown that much purely from investments, so how was it possible? Here’s how. From the billions of dollars of “contributions” coming into Social Security each month from younger workers, Social Security takes what is needed to pay generous monthly “benefits” to retired workers. It’s like getting money in the morning and paying it out in the afternoon.

That model worked for a while. For several decades, more dollars were coming than were going out (this was the case until 2010). Was that money — roughly $3 trillion — set aside in a well-protected trust fund? Not exactly. The Social Security Administration invested that surplus in Treasury bonds. In other words, Social Security lent its trust-fund money to the rest of the federal government — and the rest of the government spent it on whatever it wanted. Those surplus revenues are long gone; only Treasury Department IOUs remain.

Where will the U.S. Government get the money to pay back these IOUs to Social Security? Good question. We’re talking about a government that annually spends hundreds of billions (or even trillions) of dollars more than it takes in. (The federal deficit for 2021 is projected to be $3,003,000,000,000 — i.e., just over $3 trillion.) Needless to say, Washington is very good at borrowing; it is awful when it comes to paying back. And in the great doublethink tradition, what Congress calls a “trust fund” is actually a gigantic future liability!

Doublethink #5: The non-existent trust fund is insufficient, but we’re told Social Security has a large “surplus.”

Official figures show that the Social Security “trust fund” had a surplus of $2.9 trillion at the end of 2020. This is supposed to be reassuring, but it’s not. For one thing, the surplus has already been spent (see item #4 above). But let’s imagine the highly improbable and suppose the Treasury Department is able to fully pay back all its IOUs to Social Security. That $2.9 trillion falls far short of the level of benefits promised for the decades ahead.

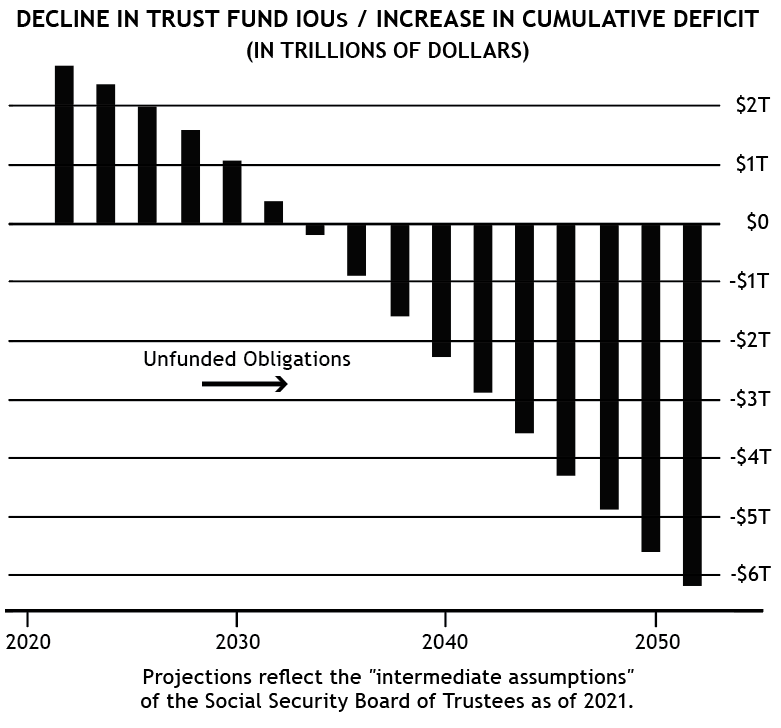

The following data and projections are from the 2021 Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds.

The situation since 2011.

The Social Security tax that workers pay on their earnings no longer raises enough money to cover the cost of benefits paid to current retirees. Social Security has been making up the shortfall by using 1) income derived from the taxation of SS benefits and 2) interest income paid on its “trust fund” holdings (i.e., Treasury IOUs).

Think of it as a family that’s spending every penny of its regular income, so it needs a second job plus interest income to support its standard of living.From now until 2034.

As of this year (2021), revenue from taxation of benefits and interest on the IOUs is no longer sufficient to make up the shortfall. To continue making payments, Social Security is starting to draw on the trust fund holdings themselves — that is, the Treasury is scheduled to pay back its IOUs to Social Security over the next 13 years. (The graph nearby shows the steady decline in trust fund holdings during this period.) As these IOUs are paid, and the money is distributed to retirees, fewer IOUs will remain to earn interest in the years to come.

Our hypothetical family is now spending down the investment holdings that have been providing essential interest income. A downward spiral is underway.

Click Chart to Enlarge

2034 and later.

The roughly $3 trillion the Treasury owed Social Security has been repaid (don’t ask me where the Treasury got the money) and all of that money has been spent on benefits. There is no more interest income. There are no more IOUs. Annual taxes (“contributions”) paid by the working population will still be coming in, and most benefits will be taxed, but those revenues will cover only about three-fourths of the annual benefits promised to retirees.

Our spendthrift family is now effectively broke — but, of course, it still has continuing (and growing) obligations. (See “unfunded obligations” in the graph.)

As bad as this sounds, it’s probably worse

Over the past four or five decades, the Social Security Board of Trustees and other experts have consistently overestimated the financial health of the Social Security program. In 1975, for example, Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Samuelson defended Social Security, saying: “Social Security is sound with a life expectancy that can be measured in the centuries.”

And yet, a brief two years later, the system was on the brink of collapse. President Jimmy Carter and the 95th Congress initiated a major rescue effort by dramatically raising Social Security taxes and trimming benefits (to which we had previously been “entitled”). We were then assured that the program was sound “for the rest of this century and well into the next one.”

But by the early 1980s, Social Security was again in deep trouble. This time a commission was appointed, headed by Alan Greenspan, later chairman of the Federal Reserve. In 1983, the commission proposed a second rescue package — this one consisting of more tax and benefit changes. They included: increasing the Social Security payroll tax from 10.8% to 12.4%, making more salary subject to the tax, gradually increasing the “normal retirement age” (at which retirees qualify to receive full benefits) from 65 to 67, and requiring some retirees to pay income tax on their Social Security benefits.

Although these changes were unpleasant, we were assured they would keep the program healthy for the next 75 years. We now know that assurance was overly optimistic.

The next rescue plan: Proposals that reduce benefits

Accurately predicting what might end up in future Social Security legislation is impossible, but we do know what sort of proposals are likely to be on the table. Many of them are described in a document titled “Summary of Provisions That Would Change the Social Security Program” (PDF) issued by the Office of the Chief Actuary of the Social Security Administration. Here are a few of the ideas that would alter benefits.

Changing the formula for calculating benefits.

One way to alter future benefits is to modify the formula used to calculate one’s basic Social Security monthly benefit. Several specific plans have already been put forward for changing the formula, including some that would reduce benefits for most beneficiaries while increasing benefits for “targeted individuals” (such as people whose working incomes were below a certain level).Modifying the Cost-of-Living Adjustment (COLA).

To keep Social Security benefits in line with inflation, current law calls for retiree benefits to increase automatically each year based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Among the proposals for change: Reducing the annual COLA by 1% — or even eliminating the COLA for people whose overall incomes are above a certain level. Another approach would alter the COLA formula so that future benefit increases would be tied to an index that doesn’t rise as rapidly as the CPI.Raising the retirement age — again.

The 1983 “rescue” plan pushed the SS retirement age from 65 to 66/67, depending on the year one was born. New proposals would increase the full retirement age to 68, 69, or even 70. (A related plan would extend “delayed-benefits credits” to age 72 from the current 70. This would incentivize people to wait longer to claim benefits.)More means-testing.

This idea, inherent in some of the proposals mentioned above, reduces Social Security benefits for those with other sources of retirement income. Consider the morality of this: higher-income earners who, over the course of decades, paid the most into the Social Security program might be told their benefits will be lowered. In effect, people would be punished for having access to other (i.e., private) retirement income.

Notice that none of these “solutions” could be justified if Social Security were truly an “insurance” program funded by one’s “contributions.” But they can be justified in the name of “fairness.” They all make it unmistakably clear, more than ever before, that Social Security is a welfare program.

The next rescue plan: Proposals that increase revenues

Addressing Social Security’s financial situation will involve boosting revenues as well as altering benefits. Revenue raisers could include:

An increase in tax rates for both workers and employers.

Under current law, workers and their employers must each pay 6.2% percent of earnings into the Social Security system. Annual earnings subject to the tax are capped at $142,800 (as of 2021), so the maximum tax paid by a worker is roughly $8,854.

(Although half of the payroll tax appears to be charged to the employer, most economists regard the entire 12.4% tax as being paid by the employee because the employer’s half comes out of the total compensation package a company is willing to offer to a worker. Self-employed workers — who don’t have an employer to pay half — must pay the entire 12.4%, up to a total of $17,707 annually.)

One tax-rate proposal calls for raising the overall Social Security tax rate to 15.8%. Such an increase might happen all at once or (more likely) in steps over several years.An increase in worker and employer tax maximums.

As noted above, there is a “cap” on the amount of earned income subject to the Social Security tax. The cap is increased over time to reflect inflation. Some recommendations call for eliminating the cap so that all earnings would be subject to Social Security taxes. Other proposals suggest keeping a cap but implementing a different tax rate above the cap.An increase in the tax on retiree benefits.

Under present law, up to 85% of a retiree’s Social Security benefits are taxable. (Lower-income earners get benefits tax-free.) One proposal would make 100% of benefits taxable for higher-income earners. (Taxing the Social Security benefits of higher-income retirees is essentially another approach to means testing, effectively reducing benefits for those who have other retirement-income sources.)Bringing more workers into the Social Security system.

Many Americans are exempt from paying Social Security taxes. These include federal workers hired before 1984, about a fourth of local and state government employees, certain college students working at academic institutions, and religious ministers who choose not to be covered. One proposal for expanding the number of workers paying into Social Security would require all newly hired state and local government employees to participate in the Social Security system.

Conclusion

Social Security’s program of benefits for retirees is over-promised and underfunded. That means we’ll be paying more and getting less in the years ahead. I wish I could assure you that if you plan to retire within the next 10 years or so, you’ll be insulated from any changes, but I can’t. At the least, I suspect you’ll face more taxes on benefits and probably a slow-down in cost-of-living adjustments.

Of course, workers under 50, and certainly those under 40, will bear the brunt of whatever changes that come. They will (1) pay more in Social Security taxes than any previous generation, (2) wait longer to collect than any previous generation, and (3) retire with lower after-tax Social Security benefits than any previous generation. As unfair as that is, tomorrow’s workers — our grandchildren and great-grandchildren — may have to pay even more, wait even longer, and receive even less. That’s the outrageous truth. But such are the consequences of living in a country continuing its evolution into a welfare state.

Given the number of Americans who will be affected by Social Security’s next “rescue” plan, it is disconcerting that the program’s financial situation wasn’t even an issue in last year’s presidential and congressional elections. Few voters want to talk about it, and few politicians are willing to bring it up. But a time of reckoning is drawing near.

For the past several decades, the approach to retirement income in America has been likened to a three-legged stool — one leg being Social Security, the second being employer-sponsored accounts such as 401(k)s, and the third being personal savings in IRAs. Perhaps we need a new analogy — or an old one: “Be prepared to stand on your own two feet.” Social Security isn’t going away, but it isn’t wise to rely on its uncertain promises. Instead, by investing diligently for your later years, do your best to carry on the once-great American tradition of self-reliance and personal financial responsibility.