After two wild weeks in the financial markets, the question on everyone’s mind is "What happens next?"

If you’ve read SMI very long, you know the answer: Nobody knows. Except this time, it’s really, truly nobody knows, because on top of the usual market-related uncertainty, we need to account for both the tangible and emotional aspects of a virus the world has never seen before. Even if we could reliably interpret solid information about the virus and the path forward to its impact on the market (unlikely in the best of circumstances), we simply don’t have enough information yet.

That’s a miserable answer because we hate uncertainty. And since "the market" is simply the massive, collective "we" in this instance, it’s no surprise that the market has hated the recent uncertainty. Thus the historic selloff over the last seven trading days of February, and the volatile, back and forth trading so far this week.

To put last week in context, it was the fifth-worst week in the last 80 years for the S&P 500. The only weeks worse than last week: 1940 (after France fell), October 1987, the tech peak in April 2000, and the financial crisis in October 2008 (hat tip: Bloomberg’s Jim Bianco).

The flip side of that coin is that bond yields have absolutely plummeted — the 10-year Treasury fell below 1% for the first time ever yesterday, while the 30-year Treasury also hit a new all-time low. That side of the equation has at least helped the bottom line of SMI investors, who were aggressively positioned in both Intermediate- and Long-term bonds prior to the moves of the past two weeks via SMI’s Bond Upgrading and Dynamic Asset Allocation strategies.

Still, that’s small comfort when reviewing the stock market situation, and particularly that ominous list of priors noted above.

The broader context

Howard Marks has long been one of my favorite investment writers because of his ability to logically distill situations to their most important points. He did a great job of this in regards to the coronavirus and its impact on the stock market in a recent memo (PDF). If you have time, I encourage you to read the whole thing, as it’s probably the best analysis of the current market situation I’ve seen yet.

Marks makes the point that when this whole coronavirus episode is over, it’s unlikely to have permanently changed life as we know it. Like other seasonal diseases, we’ll likely develop a vaccine and learn to deal with it. Furthermore, if that’s the case, it’s likely true that U.S. businesses haven’t permanently lost 10%+ of their future income streams. Which would suggest that the 10%+ discount applied to the market today vs. two weeks ago might represent a buying opportunity.

However, as Marks also points out, that argument assumes stocks were priced reasonably two weeks ago. If they weren’t, there’s no reason to necessarily assume they’ll bounce back to their former valuation status.

This is largely what I’ve been focused on as well in trying to think through the current situation. A week before the stock market would hit its eventual peak, I posted an article that included a chart of "the Buffet Indicator," which showed the ratio of total U.S. stock market value to GDP. Here’s that chart again, as it stood on Feb 12.

At the time, that ratio was somewhere around 156%-158% (I don’t remember exactly and it’s hard to make out precisely on the chart). After the sharp correction of the past two weeks, this indicator has declined all the way down to...144.6%. (That’s not shown, but you can see an updated chart here.) Looking at that chart, it’s abundantly clear that 144.6% is nowhere near bargain territory.

Now don’t misunderstand me here. That doesn’t mean the market is necessarily going to fall further. It’s just that the idea that "stocks have gotten cheaper so it’s time to buy!" that has been the mantra of the past decade’s bull market feels like a stretch at this point. If the coronavirus doesn’t put a major crimp in U.S. economic activity over the next few months, and if the U.S. economy avoids a recession, then the market may bounce right back and we’d look back at early March as a potentially great buying opportunity.

Those are some pretty big "ifs" given what we still don’t know about the virus and what our response to it will entail. The Federal Reserve wasn’t waiting around to get more data: despite only having 1.5% of potential rate-cut ammunition to use in the case of a recession, it made its first emergency rate cut in 12 years yesterday (meaning a cut between scheduled meetings). And after making only quarter-point moves up and down for many years, it cut rates by half a percent, from 1.5% to 1.0%.

Given that the Fed has reduced rates an average of 5% during past recessions, the fact that they have only 1% left to work with isn’t reassuring. But it does signal loud and clear that the Fed’s leaders felt a big move was warranted to try to stem market fear about the coronavirus and its eventual impact.

Two paths forward

If this is just a quick market correction, we’ll be glad we didn’t get an Upgrading 2.0 signal and that Sector Rotation stayed invested aggressively. We may wish we’d taken advantage of the dip to buy a little (for those with cash on hand), and obviously DAA’s pivot to safety will cause it to lag. But big picture, that path is relatively painless from here.

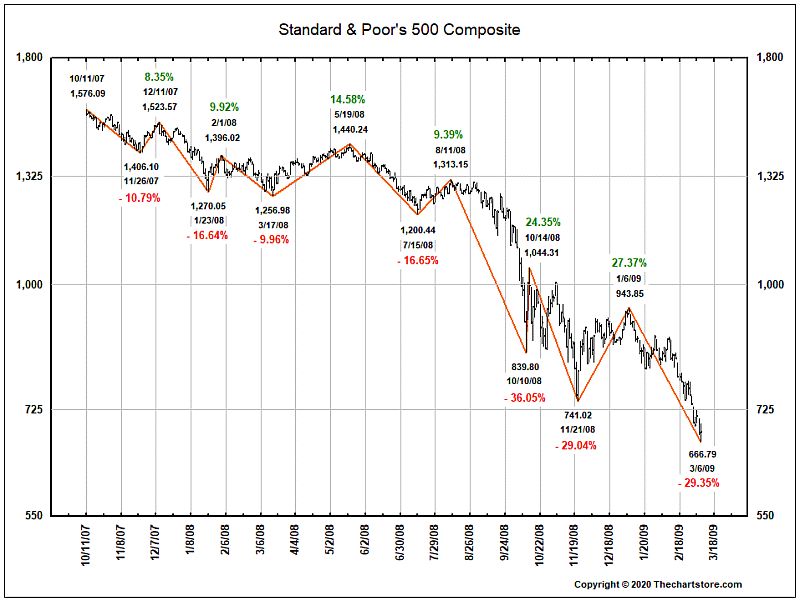

On the other hand, if this is the beginning of the first bear market in more than a decade, we need to be prepared for what’s ahead. Consider the following chart of the 2008 bear market:

Click Graph to Enlarge

Bear markets are known for sharp counter-trend rallies. You can see six of those labeled in green on the chart above. This is actually how long, drawn-out bear markets are possible — they draw in buyers every so often by making them believe the worst is over. So in the 2008 example above, the first move of -10.79% was followed by a bounce higher of +8.35%. Then the market fell another -16%, only to bounce back +9.9%. Each rally occurs as events provide reason for optimism that the worst may be nearly over.

Translating that to today’s situation, it’s not difficult to see that pattern potentially at work already. We’ve had an initial drop of -12.8%, but then a solid bounce of +4.6% (so far), and there are plenty of voices saying it’s time to "buy the dip."

And we can’t rule out the idea that they’re right! But the risk/reward balance of rushing to buy the dip here still feels skewed, with the downside risk significantly larger than the upside reward. That’s why I wrote this weekend that I wasn’t unhappy to have a "split decision" between our major strategies, with one having taken decisive defensive action but the other not responding yet. With so much unknown, not having all our eggs in either the "bounce back" or "bear market" baskets seems like a good place to be.

Aggressive investors with long time horizons may want to nibble a little here. But for most of us, waiting patiently until our mechanical strategies can confirm the trend in one direction or the other — hard as that may be — seems like the smart approach.